Drug Wars, Video Games, and Ginga: Carlos Amadeu and the changing face of Brazilian football

A fortnight ago, on September 23rd, war erupted in Rocinha, one of Rio's largest favelas as rival drug gangs sought to seize one of the most lucrative slices of market in one of the world's most populous cities - when a profit margin of 3000% is on the line, people can go a little over the top about it - and the Brazilian government decided to send in it's army to quell the violence. (That ought to give you a good enough idea about the kind of firepower these gangs pack, the local police simply stand no chance against them)

The move has not proved to be completely effective, and the air in Rocinha is still laced with the tension that always preludes impending violence and death.

A recurring theme in modern Brazilian life, the violence unleashed by both the government and the gangs have escalated many-folds over the years (the debate on how best handle it, I'm afraid, must be left for another day) - there are around about 50,000 deaths a year in the country, and more than two-thirds of this number has been linked to drug-related violence. Back in 1980, before cocaine had made its entrance into the marketplace, the homicide rate in the nation was 11.7 per 100,000. By 2010, the rate had more than doubled to 26.2 per 100,000. In just 30 years, and in the wake of some rather repressive policies of containment and control, more than a million Brazilians have lost their lives in a war that seemingly has no end.

In absolute numbers, Brazil is the deadliest place on the planet outside Syria.

Analysts say that in 2015, Brazil generated $2.4 billion in sales of digital [video] games, a figure that made the nation the world's fifth largest digital games market on the planet... and considering the exponential growth that video game manufacturers have seen in the region over the past decade, it isn't much of a stretch to assume that sales numbers would have left the $3 billion barrier by the wayside quite a while ago. Considering just how restrictive Brazilian tax laws are with respect to virtual games, you can make your own conclusions on just how much of the demand for console and mobile games are met via the highly popular mediums of bootleg markets and online piracy.

And the most popular game in the nation?

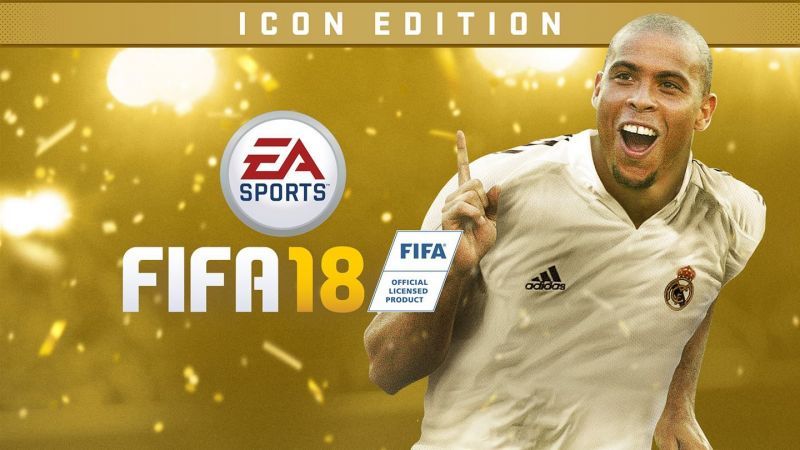

EA Sport's FIFA Franchise.

The world's most popular video game, FIFA has pervaded the national consciousness like nothing else and every year the number of youngsters who get hooked on to this increases exponentially (...and old people, age is no bar for e-sports) and EA knows this - hence their push to add Ronaldo (the original) as the first cover of their inaugural "Icon" edition and their decision to increase their already massive marketing and sales presence in the region.

Brazil loves it's FIFA, and there's simply no two ways about it.

Every nation on this planet that has seen at least a modicum of violence being unleashed against their populace has their own distinctive style of martial arts. China has Kung-fu, Japan Karate, Israel has Krav Maga and the moment you see it, you know what it is - a method of fighting, whether in attack or self-defence a medium to inflict violence and pain... in Brazil, though, you'd never guess it.

You see, the people there, during the height of the Portuguese rule, had to hide the fact that they knew a martial art - so as to avoid spooking the all-too-trigger-happy colonialists -and they did it by, well...by making it a dance.

Et, Voila! Capoeira was born.

Known for intricate maneuvers - combinations of spins, kicks, and other techniques - that are quite impossible to predict, Capoeira is a mesmerising, near-hypnotical martial-art... the quintessential rhythm so evident in it coming from it's most fundamental movement, the basis of the Capoeira, the Ginga (literally, rocking back and forth)

Drug wars, EA Sport's FIFA, and Capoeira' Ginga.

What in the blue hell could these three things have in common?

Well... Football.

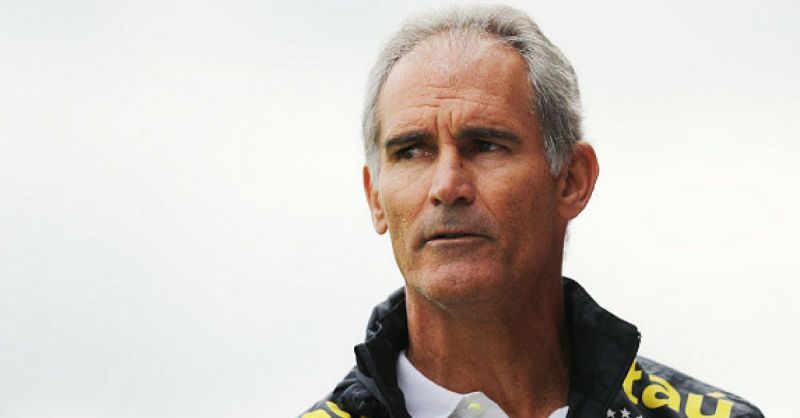

That, at least, is what the genial gentleman who coaches the Brazilian national under-17 team believes.

Carlos Amadeu - 52, former defender at Bahia and Galicia, former coach of Vitoria's highly successful U-20 and outfit, still possessed of a killer first-touch (if his team's training sessions are anything to go by) , and current head coach of the Brazilian u-17 national team - opened up to us about the changing face of Brazilian football... and about just what has brought about that change...

"The Brazilian players, they are suffering from the consequence of all the things that are happening in the country right now in our country. Some years ago we had the freedom to play a very [open, spontaneous, creative] style of football, we didn't have violence. These days, we have a lot more violence, we have these drug [wars] and we lost the street space to the violence"

So has the creativity that marked Brazilian football as different, the sheer love of the game, has that all disappeared for good? Has the Ginga that Nike used so successfully to connect Brazil's love for dance, music, and football, the Ginga that inspired the term Joga Bonito, the Ginga that the world views as inseparable from the Brazilian game... has it all but vanished?

"We still have this but in less quality. We continue having this Samba, the Brazilian Carnivale, the Ginga, but in less quantity because of the violence, because of the virtual games - we have so many video games like FIFA now - people are more inside their homes than outside, they are having less movement outside."

You see, the spontaneity, the sheer joy that we so readily associate with Brazilian football stems from the unpredictability that only street football can bring out in a football.

The (original) Ronaldo once said, "Every time I went away I was deceiving my mom. I'd tell her I was going to school but I'd be out on the street playing football. I always had a ball on my feet."... he attributed his lightning-quick feet and penchant for the kind of tricks and flicks that most other footballers simply couldn't bring themselves to imagine as possible to the years he spent honing them while beating opponents on the tricky, tight, spaces that the streets provide.... these are the self-same street 'pitches' that moulded Pele ("We used to [make] a ball with socks,” the great man once reminisced. “Get my father’s socks, my mother’s. Then we’d fill them with paper and play in the streets.”), Garrincha, Didi, Rivellino, Zico, Romario, Ronaldinho... and even Neymar.

To think of them as disappearing is heartbreaking, for no football team has ever quite captured the imagination of the sports-loving world quite like the men in canary yellow.

A Seleção just wouldn't be the same without Ginga.

But Amadeu is not a world-weary cynic who spreads doom and gloom - he'd make a horrible candidate for coaching youngsters if he was, wouldn't he - and as much as the creases on his face are lined with fear, a worry, about what the future holds for his nation and the sport he has dedicated his life to, the sparkle in his eyes simply cannot but underline the positives of the changes that are taking place in the system.

"But we are also more organised in our clubs, our academies to practice football, there are better training facilities - the rest is but a natural consequence of what's happening in the country"

A realist, then, not a pessimist. Pretending a problem doesn't exist doesn't make it go away, and acknowledging it is always the first step to finding a solution - and Amadeu is on the right track on that one.

Besides, he doesn't fear that Ginga will escape the Brazilian game just yet. He sees it as his responsibility to ensure it doesn't. After all, he says, isn't that why the world loves watching us so much?

"If you stimulate it, it is still something you have in Brazil, more than in other countries. What I tell my players... what I try to show them is that they are clever, that they have some characteristics different from other players around the world"

So what, exactly does he tell these youngsters - who arrive at his doorstep a bundle of natural technique, imagination, and pure, unfettered skill?

"Principally in the last [third] of the pitch, the forward line, what we are trying to teach them is to think more about the game, to analyse the opponent, to be more clever inside the pitch"

He also views it as important that they do not coach the natural game out of the players, to make them machines... "they have to have an autonomy to decide for themselves what to do once the match starts. So it's just the little things, the little adjustments that we try to teach them because the other things they already have"

As Victor Bobsin, central midfielder for Brazil and Gremio U-17 (and a player who wants to be like Sergio Busquets; a Brazilian kid who wants to be like Busquets... as I live and breathe!) confirms, "Amadeu is a coach who asks to be really strong as a defensive unit, as a system, to keep possession of the ball, and going forward to be objective"

After all, it is goals that win matches.

A very real fear, though, is the impact that European clubs, and their vast swathes of money, are having on the development of the Brazilian footballer, but Amadeu does not blame them for any perceived loss of the 'traditional' Brazilian style of play", or for stealing his players way whilst still in the proverbial cradle (The fact that Real Madrid struck a £38 million deal with Flamengo for the then 16-year-old Vinicius Jr. doesn't become any less stupefying the more we think about it; and he's just the tip of the iceberg), but Amadeu is not overly worried.

"Everything has an effect. We are affecting them, and they are affecting us, but it's not only a negative thing... it can be positive, for us we are learning another way(s) of playing, other [methods of] tactical organisation and thinking... for sure it would be better if the players could stay with us until they are 24-25; but the world is changing, Europe has the money, so we have to understand this reality and try and take the positives... we know the money, the tournament, it's all better organised in Europe"

With this kind of clarity in thought, this far-reaching understanding of the very soul of Brazilian football and the various problems that plague the beautiful game in a modern behemoth struggling to bridge the yawning class-divide that is there for everyone to see, struggling to contain the mass violence that only cocaine has the power to unleash, struggling to maintain it's identity as the world's quintessentially most-fun loving nation, Carlos Amadeu is the perfect man to be put in charge of moulding the minds of the young boys who flow into the Brazilian football system dreaming of making it big.

It's because of people like Amadeu that the Beautiful Game will live on.

Forever.

Viva Amadeu! Viva Joga Bonita!