Football goes Stateside: The 1994 FIFA World Cup - Part 6

This is something Shakespeare couldn’t have scripted in his wildest dreams. It is drama that Hamlet can only hope to equal.

The World Cup final is a curious beast, because for football’s most monumental spectacle, it’s often very far from being the best game of the tournament.

That may be a little surprising, per se, but it really is quite an accurate insight into the dynamics of tournament football. The beautiful game ought to frame a maxim to that effect: “As a tournament progresses, it becomes less and less about who does the most things right and more and more about who does the least things wrong”.

A day of reckoning

On June 30, 1992 the World Cup final was awarded to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, a sprawling 90,000 seater in Los Angeles county.

The grand stadium brought with it a sense of occasion, an epic sporting battle to be fought out on American football turf, and in hot conditions under largely clear blue skies sprinkled with some white clouds.

July 17, 1994 dawned, in no way significantly different from the 30-odd days that preceded it.

Over 94,000 people jammed into the Rose Bowl that day saw Brazil walk out under inviting Californian skies. They were led by Dunga, who had been emphatically roasted by the Brazilian press in the post mortem of a disastrous Italia ’90.

The man heading the Italians, though, induced gasps of shock and amazement among those watching.

Italians walking wounded

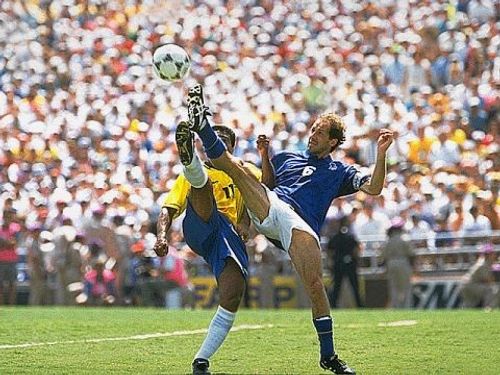

Regular skipper Franco Baresi had damaged his meniscus against Norway in the group stages and did not take part in subsequent games. A mere twenty five days later, at the age of thirty four, he was back in the heart of the Italian defence, marshalling his troops like an able general.

The country had called for Baresi, because Italy’s defence was looking desperately short of numbers following the suspensions of Costacurta and Tassotti (who had been handed a retrospective eight game ban for a violent elbow on Luis Enrique in the quarter finals), and he responded immensely.

Baresi was not the only Italian to arrive in Pasadena looking like he needed a hot shower and a bed instead of the energy sapping tension of a World Cup final. The talismanic Roberto Baggio had a hamstring problem, and was forced to take painkillers in order to even make it onto the pitch.

Exhausted and with black tape wound tightly around his right thigh, Baggio looked out on his feet before the game even began, but he had to soldier on.

This rematch of the 1970 final had the world expectant. That this would be the contest of all contests. That sporting brilliance would be decisive in rounding off a brave foray into the land of basketball and baseball. And in closing the door on the summer of 1994 perfectly.

If only.

The game seemed doomed from the start. Brazil and Italy scrapped around aimlessly in the middle, each knowing that midfield dominance would do nothing about the defensive solidity of the other. The game, it seemed, would only be settled in the penalty boxes.

Both teams held their collective breath. Neither was particularly keen to commit, instead hoping Romario or Baggio would break the deadlock with their instinctive brilliance.

Baresi put in another aggressive performance, scarcely identifiable as an athlete who had suffered a debilitating injury less than a month prior. Brazil simply could not get past the impregnable human shield.

The chances, as a consequence, were few and far between. Claudio Taffarel repelled Daniele Massaro’s first half effort, but it was Gianluca Pagliuca in the opposite goal who almost lost the game for Italy. Fifteen minutes from the end, he came catastrophically close to gifting Brazil a goal, but the ball, having spilled out of his hands, tapped against the post, allowing Pagliuca to scoop it up gratefully.

The game finished 0-0, but a couple of isolated opportunities came in extra time as well. Pagliuca blundered once again, but Bebeto royally scuffed his chance. Romario too missed a simple tap in.

Taffarel blocked Baggio’s long range effort, and then saved once again in the dying seconds, with Baggio unmarked in the penalty area with the ball at his feet.

Penalties

The game was going nowhere, and penalties were a mercy in the end.

With the score at 2-2, Daniele Massaro’s shot was saved by Taffarel. Captain Dunga then got some retribution, converting a third for Brazil.

The equation was now as clear as the Pasadena skies. Roberto Baggio had to score, and then hope Brazil didn’t convert their final kick.

Baggio had converted to Buddhism while still in his teens, after initially damaging a knee that would bother him for years, acquiring reorganised psychic balance and a new perspective on life.

Baggio stepped up, determined to finish the job before fatigue finished him. He later spoke of how the tiredness clouded his mind and physically affected his kick.

Famously, Roberto Baggio then blazed his shot over the bar, and Brazil were world champions again.

Brazil dedicated their triumph to Ayrton Senna. The nation had been mourning since his untimely passing in May, and Brazil’s World Cup win was a fitting tribute to him.

The Italians, on the other hand, were absolutely distraught. It was quite moving to see the hard man Franco Baresi, having battled through the pain, reduced to inconsolable tears.

On the faultlines of history

Ultimately, this hugely disappointing final will not be remembered for the football. It will, instead, be recognised as a crucial date in football history.

The Brazil side that travelled to Spain in 1982 were a vibrant attacking unit and seemed destined for greatness. Those who had the privilege to witness their exploits still speak of them in awe.

When they came up against a floundering Italy in the second round, they were expected to flatten them. But a fantastic see-saw encounter saw Italy land the killer blow about 15 minutes from time to down the high flying Brazilians 2-3.

Brazil were absolutely traumatised by that defeat and subsequently decided to swap a flash of inspiration and a blur of the feet for a crunching tackle and two defensive midfielders. The vowed never to be outdone quite so naïvely again.

USA ’94 was essentially validation for Brazil’s new philosophy. It was proof that this new approach would get them the results that they wanted. The game lost an inventive spirit that evening in Barcelona, but Brazil were the ones who cared the least.

But really, despite all that, Romario was truly Brazil’s hero throughout the tournament. He had a hand in 10 of Brazil’s 11 goals in the tournament, and was able to put his differences with Bebeto aside to deliver emphatically on the grandest stage of them all. The Golden Ball was simply the icing on the cake.

Incredibly, he was matched stroke for stroke by Baggio.

So near yet so far

What, then, of Baggio?

Surely it would not be outrageous to compare him to Diego Maradona in 1986? El Pibe de Oro’s emblematic performance in Mexico that summer, dragging a shifty looking Argentina side to the World Cup title, was something Baggio came very, very close to emulating.

It is a brilliant story when you think about it. The man (in the eyes of some) solely responsible for ensuring Italy’s defeat in the final was also the man solely responsible for getting them that far. It is a mystical tale only sport can write.

The World Cup was a little bit like the first WrestleMania. There was an enormous amount riding on it and had it flopped, it would only have brought disaster. It was the enthusiasm of the fans and this quartet of footballers who ensured that was not the case.

There is plenty of other trivia from this World Cup. The ‘baby rocking’ celebration, was the proud father in Bebeto letting the world know after his goal against the Netherlands. It took the world by storm, fathers in subsequent years displaying it to the point of oversaturation.

Marc Overmars’ blistering speed saw him named the best young player, but USA ’94 is strangely a footnote in his decorated career.

And to cap it all off, Brazil’s squad for the World Cup had the usual faces, but there was a much hyped 17-year-old amongst them. The prospect of his bow on the world stage was mouth watering, but he did not make a single appearance. His name was Ronaldo.

But ultimately, it all comes back to Roberto Baggio. After a lacklustre performance in the group stages, the rescue began against Nigeria. He never looked back.

His Buddhist serenity and terrifying precision was matched only the coolness and unerring inevitability of his finishes. He was a star.

Amidst the fury, the noise and the light that raged around him, Baggio maintained his poise at all times. He seemed to slow down time. And his greatest gift was his ability to make a stadium of 90,000 people in a football-phobic country look at him all at once. It seemed as though 11 v. 11 had been reduced to 1 v. 11.

Baggio never won the World Cup. But one wonders if the ache of never winning the big one can ever be matched by the missed penalty.

It seems forgotten that even if Baggio had scored, Brazil could have won it with their next penalty. One wonders if Baggio would have substituted that for a lifetime of peace of mind.