Moacir's last sigh

“Only three people have, with just one motion, silenced the Maracana – Frank Sinatra, Pope John Paul II and me.”

Alcides Ghiggia described the immediate aftermath of his action with a pomposity that few would begrudge as unfit for the occasion. Ghiggia had scored the goal that gave Uruguay the decisive lead in the 1950 World Cup final against Brazil, in the Maracana, in the presence of 200,000 Brazilians who had gathered to watch what was considered a foregone conclusion – Brazil beating Uruguay to win the World Cup.

The result disorientated Jules Rimet himself to the extent that he handed the cup to Obdulio Varela, the Uruguay captain, amongst a throng of spectators and crying Uruguayan players without any fanfare.

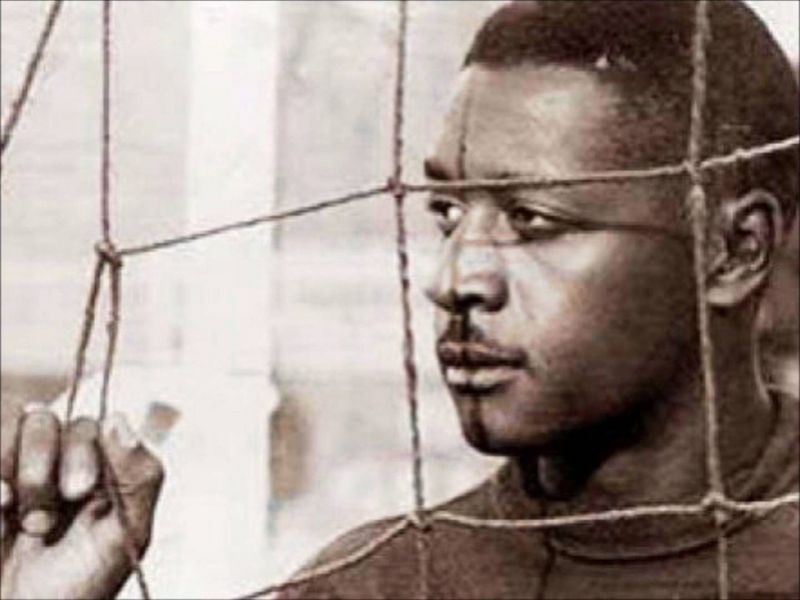

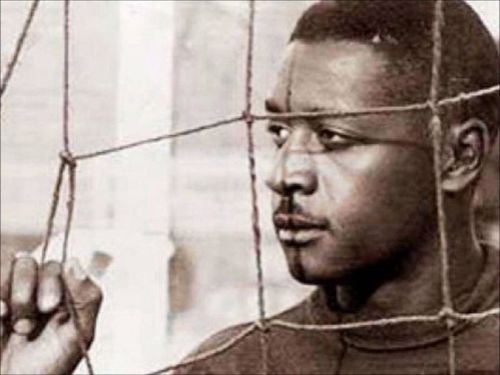

Moacir Barbosa Nascimento, the 29-year-old Brazilian goalkeeper, had been dealing with Ghiggia’s crosses from the right flank when the latter made his weaving runs before lobbing the ball in.

Ghiggia had provided the assist for the first goal scored by Schiaffino. A similar run made Barbosa, who was only 5’9” (this was before it became the norm for goalkeepers to be towering figures), move away from his near post expecting a cross. Ghiggia then shot at the narrow gap between the keeper and the goalpost and the ball found its way in.

The goal was, and still is, the most traumatic in Brazilian football history. So much so that there is an eponymously named short film in 1988 in which the lead character goes back in time to stop the goal. The effect of the goal on the Brazilian football psyche was put into perspective more than half a century later, in 2005, when Darwin Pastorin compared the bullet that killed Kennedy to the goal in his book, The Last Save of Moacyr Barbosa by saying, “The same drama...the same movement, rhythm...the same precision of an inexorable trajectory. They even share clouds of dust - one from a gun, one from Ghiggia's left foot.’”

Then ensued a torrent of public angst, greater in magnitude than what was seen after the 2014 humiliation, in Brazil, at the hands of Germany.

The Brazilians had been dominant throughout the tournament, with Ademir being the leading scorer and Jair and Zizinho ably assisting in attack. A fan’s anger laced with copious amounts of irritation and resentment when his/her team, which was supposed to have won emphatically, goes on to lose, does not dissipate as easily as after a loss which was excusable, even expected, as against Germany without Neymar and Thiago Silva.

Barbosa was culpable for Ghiggia’s goal, which translated to him being guilty of losing the Cup for Brazil in the public eye. The tremendous public rage was channelled and there was a figurative lynching; something which Indian cricket fans would know via sentiment if not detail. Chetan Sharma, anyone?

Barbosa was generally accepted to be the best choice as the goalkeeper for Brazil for the World Cup. He had an impressive CV to stake a claim to this position. He was a part of the 1949 Copa America winning side which thumped Paraguay 7-0 in the final. He was the goalkeeper for the Vasco da Gama side which had won the Campeonato Carioca – the state championship in Brazil – in 1945, 47, 48 and 50 as well as the precursor to the Copa Libertadores in 1948. He was also voted the best goalkeeper in the 1950 World Cup.

Why, then, did he fall out of favour so drastically? The racial undercurrents in Brazilian society shed some light on this. Moacir Barbosa was black. Black people were generally ill-favoured in Brazil at the time; they were perceived as the weak section of society, impeding the social and financial advancement of Brazil.

Gaspar Dutra, the Brazilian president who had come to power after overthrowing Getulio Vargas in a coup, had lost the election to Vargas again, but his social stance had done little to dispel the public's perception of black people.

This was not the Brazil that would gradually accept the fact that their best footballers were black, such as in the 1958-62 double World Cup winning team consisting of Didi, Pele, Garrincha, and Nilton and Djalma Santos. Such was the stigma associated with Barbosa being black that Brazil started with no black goalkeeper till Dida played for them in 1995 and none in the World Cup till Dida again became the first choice in 2006.

What followed was a Chak De India-esque tale of rejection and ruination. Unlike Chetan Sharma, and SRK’s Kabir Khan though, Barbosa never got a shot at redemption. He continued to play for Vasco da Gama for a few more years, with departures to Bonsucesso and Santa Cruz in between.

He even won a few more trophies with Vasco but the Brazilian public did not warm to him. He eventually retired from professional football in 1962.

Even after Barbosa had been, weirdly, given the goalposts from the Maracanazo which he went home and summarily burned, the ghost of the match could not be exorcised. Although the keeper says the worst he felt was when he heard a mother tell her young son ‘there is the man that made Brazil cry’ after seeing Barbosa in a shop, the most telling rejection was when he was refused a meeting with the Brazilian squad of the ’94 World Cup by none other than Mario Zagallo, a World Cup winner as both manager and player for Brazil, who thought the keeper might bring the team bad luck.

Supporting a team is essential for following most team sports. Adding an element of nationalism to supporting the team might uplift the morale of a generally unhappy populace during a tournament or a match, but it rarely works out well beyond that. If things go awry, it can ruin the life of an honest, talented professional who made a mistake, as is a sportsman’s wont.

Barbosa was living in penury in 1997, after the death of his wife, till Vasco da Gama found out about his plight and gave him a stipend to make ends meet. He died without any form of public consolation in 2000, condemned to ignominy till death.

His story has been oft-quoted to show the dichotomy of sports fanaticism and has been covered by a few newspapers and magazines (mostly after his death), most eloquently yet with brevity in Eduardo Galeano’s brilliant book Football in Sun and Shadow. It serves as a reminder that we shouldn’t take Bill Shankly seriously when he said football was more than a matter of life and death.