Mourning the death of the classical 4-4-2

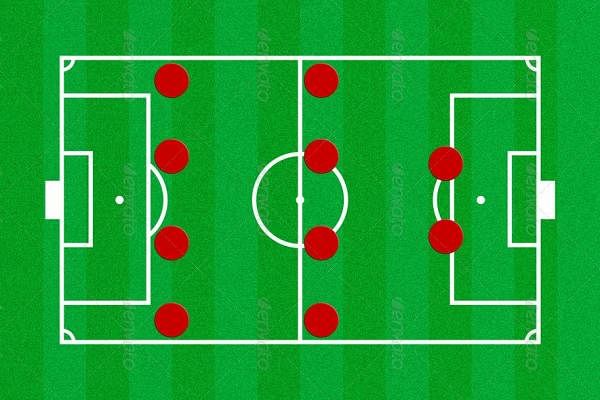

8:00 AM. My friend and I decided to hang at his place and play FIFA 15 on his PlayStation, with the bean bags, consoles and popcorn, in full measure. I love the Bayern team in the game and play them all the time, while he’s a hardcore PSG fan. The wagers were out, the lights were on and the teams were ready. I was playing Thomas Muller and Robert Lewandowski up top, with sets of four midfielders and defenders behind them. He played the same, with the otherworldly duo of Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Edinson Cavani leading the pack. Game on.

9.00 AM. After four games, we paused for a while. Upon pausing, the screen showed PSG’s team-sheet in full splendor. What a perfectly balanced team. Two pacey wingers in Ezequiel Lavezzi and Lucas Moura. A genuine deep lying playmaker and an industrious box to box man in midfield – Marco Verratti and Blaise Matuidi is a central midfield pairing made in heaven.

The four at the back picked themselves, with him playing Serge Aurier and Lucas Digne on the flanks, while David Luiz and Thiago Silva marshalled the defence. I looked at the squad with envy. And then, I started wondering. Why do they play the 4-3-3, when they have a squad so wonderfully suited for the 4-4-2? And mind you, this wasn’t Laurent Blanc going nuts; sadly, this is the norm today.

11.00 AM. I was back home and was reading the book I consider my Bible, Jonathan Wilson’s “The Anatomy of Liverpool”. One quick search on the author and I found myself being fascinated by the concepts behind his award-winning book “Inverting the Pyramid”. From Vittorio Pozzo’s Italy to Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan, the book was the Britannica of football tactics. Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan, What a team. Probably the greatest team of all-time. And their formation? 4-4-2.

Serie A titles, Intercontinental titles, European Cups, that team had won everything. Watching a few videos of that team, I was startled by how high they pressed. The team attacked and defended as a unit, with Ancelotti-Rijkaard and Gullit-Van Basten standing out for their pressing and work-rate. 4-4-2 was perfect for them, as it was for many of the greatest teams of the late ‘80s and throughout the ‘90s.

Fabio Capello’s Class of 1994, Sir Alex Ferguson’s successful team of the ‘90s with Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole up top, the great Barcelona team of the era with Romario-Stoichkov leading the line, Ronaldo-Bebeto for Brazil; needless to say, the formation ruled the roost. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing and reading. It was the go-to formation of nearly every successful manager of the time. A few hours on YouTube and I was transfixed by the football played by these great sides. Time flew.

The signal of the end

2.00 PM. With every rise, comes a fall. It is as plain a fact of life as any. Hypnotised by the mesmerising football played by the exponents who took the formation to its zenith, it was time to discover the other side; time to see the formation hit rock bottom, the nadir. It was World Cup time in the summer of 2010. England was facing Germany in the World Cup R16, with the man at their helm being Fabio Capello, one of the finest proponents of the formation.

90 minutes later, his beliefs, philosophy and tactics had been torn apart by the rampant Die Mannschaft, playing the solid 4-2-3-1, which was in vogue at the time, and still is, to a certain extent. A certain Mesut Ozil exploited the gap between the imbalanced and pedestrian English midfield and defence. Four goals and a zillion postmortems later, the British journalists proclaimed in typically outspoken fashion – “The 4-4-2 is dead”.

4.00 PM. Reading about the perceived death of a formation that was once so successful wouldn’t be complete without knowing the reasons. One quick look at all the successful teams of the last decade or so, and it was there for everyone to see – not one, not two, but a multitude of reasons came together to effectively suck the life out of the 4-4-2.

- With the arrival of a new breed of proactive managers like Pep Guardiola, Ronald Koeman, Mauricio Pochettino, Joachim Low and others, the game became less direct and more intricate. Gone were the days when the wingers waltzed down the flanks without a worry in the world and full backs were nothing more than auxiliary centre-halves. They were replaced by wingers who tracked back and full-backs who overlapped, with an effective swapping and changing of duties, leading to a game more reliant on short, incisive passing.

- Along with a change in roles, the playing style of wingers also changed. One-dimensional wingers like Milos Krasic, Antonio Valencia and Aaron Lennon could no longer reach the very top; it was the time of Franck Ribery, Eden Hazard, Arjen Robben and the like – it was the time of inverted wingers. Wingers could no longer claim a spot in the side by just sprinting and crossing. Cutting in, passing, assisting and tracking back was and is the order of the day. To put things in a nutshell, wing play is no longer the same.

- Whether it be possession oriented managers like Guardiola and Co or defense-minded ones like Mourinho and Simeone, one thing remains the same – the added emphasis on a midfield with numbers. While the Bayern supremo has taken it to new levels playing even 6 and 7 midfielders at a time, most of them employ at least five. This has resulted in players being expected to do specific roles.

For instance, take the Chelsea squad. They play a fluid 4-2-3-1 formation, which morphs into a 4-5-1 or 4-3-3, as per the requirements. Nemanja Matic is the destroyer in the middle of the park – their new Claude Makelele. Cesc Fabregas is the deep lying playmaker, their pass master. Oscar plays just behind the striker, donning the role of the No. 10. Willian is the more direct and hardworking winger, someone who chips in with the odd goal. And Hazard is the creative hub of the team, leaving the defenders in a daze as he cuts in from the left. - With such high degrees of specialization being the norm, the breed of box to box midfielders, arguably the pivots around which the 4-4-2 revolves, slowly started dying. Players in the mould of Roy Keane and Clarence Seedorf were and are still hard to find. Players like Yaya Toure and Arturo Vidal are the rarities today. And with the death of multi-functional midfielders, came the death of the formation that they were such an integral part of.

- Probably the most important point though, was the change seen in the art of defending. It was no longer about burly and intimidating men delivering crunching tackles and heaving the ball into the air towards the gleeful feet of the No9s. The role of a defender in today’s game is much more complex, with ball-playing centre-backs being an essential requirement for every team. Needless to say, this has resulted in increasing number of errors and mistakes in judgement, not to mention the huge gaps between the defence and midfield that is exploited when teams are caught on the break.

Hope for revival

These factors have conspired and coincided at more or less the same time during the noughties to consign the 4-4-2 team sheets into the done and dusted folders, more or less. The important part here is “more or less”. They haven’t become entirely redundant. Is there a chance for revival? Let’s see.

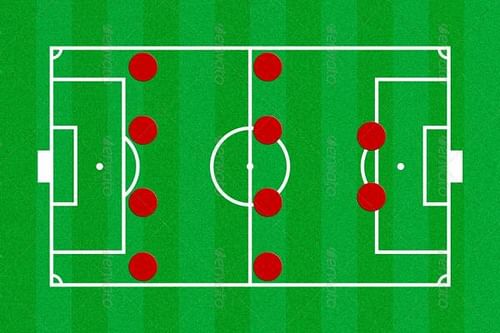

8.00 PM. After delving deep into the how’s, why’s, pros and cons of the waning influence of 4-4-2, it was perhaps time for me to mourn its death before going to sleep. Not so fast though, as one look at the 2013-14 season gave me renewed hope. Jonathan Soriano and Alan for Salzburg, Sergio Aguero and Alvaro Negredo/Edin Dzeko for Manchester City and perhaps most importantly, the SAS (Daniel Sturridge and Luis Suarez) of Liverpool were all fantastic advertisements for the strike partnership system. Needless to say, all three teams employed the 4-4-2 to great effect, instilling new hopes in the hearts of purists, who grew up watching the formation wreak havoc.

9.00 PM. It ended up being more or less of a false dawn though, as various factors worked against these clubs, resulting in them not playing the 4-4-2 anymore. Instead, a new variant of the formation was on the rise, with one of the withdrawn strikers also playing the role of a winger or trequartista, duly assisting the No. 9, as and when required. The examples of Nabil Fekir and Alexandre Lacazette for Lyon, Lionel Messi and Neymar for Barcelona and Cristiano Ronaldo-Karim Benzema pairing at Real Madrid, were all examples of a different, yet tactically flexible variant of the traditional strike duo.

10.00 PM. So, it was time for me to rest, to sleep. And no, the brains behind the beautiful game hadn’t yet laid the 4-4-2 to rest. The time to play the dirge hadn’t yet come. The time to mourn hadn’t yet arrived. And unlike this article, the 4-4-2 hasn’t yet become a past tense phenomenon. Here’s to hoping it stays for good. Cheers.