Silver, gold and the ultimate lottery - The evolution of extra time in football

It was the 17th of July, 1994. In front of nearly a 100,000 strong sea of yellow and blue, at the Rose Bowl, Pasadena, football served out one of its most poignant moments of the 20th century, as Brazil took on Italy in the FIFA World Cup Final. After 90 goalless minutes, the match went into extra time – the first time it had reached that stage since Ernst Happel’s Oranje dream team suffered the ultimate heartbreak against Cesar Luis Menotti’s Argentina in 1978.

This time though, the match went a step further, as both teams stayed at loggerheads after the stipulated two hours of football. Penalty shootout lay ahead. After skipper Dunga put Brazil a goal in front, ahead of Italy’s last kick, all eyes were on one man – Roberto Baggio. The Ballon d’Or holder was the player any fan of the game would’ve put his life on, to score the kick. Such was his aura, such was his form.

A few seconds later, however, everything had turned on its head. The whole world watched in shock as a crestfallen Baggio fell to the ground after missing his penalty. Brazil had become the first team to win the World Cup after a penalty shootout. The Divine Ponytail had become the first high-profile victim of football’s version of the Russian Roulette.

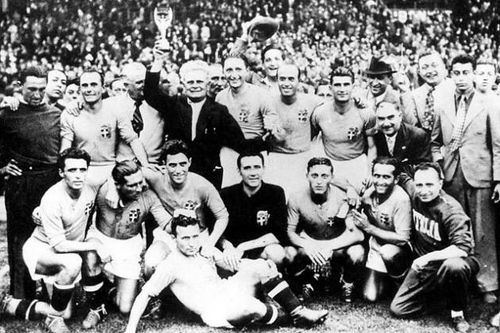

Over-time in any association sport has always been a cauldron of controversy, courage and a cocktail of emotions. It brings out the best and worst in sportsmen. And extra time in football has been, and still is, a living testament to this. Right from Angelo Schiavio’s 95th-minute winner that gave Vittorio Pozzo’s fabled Azzurri team their first ever World Cup win in 1934 to James Troisi’s sensational winner that propelled the Socceroos to their first ever Asian Cup earlier this year, the beautiful game has seen all kinds of spills and thrills, as battered minds and bruised bodies are put through more than they can take. To see its vague origins, let's go back in time.

The beginning of the evolution

The 1877-78 season was an epochal one in the history of English and indeed, world football. West Bromwich Albion was founded in the English Midlands while Manchester United, called Newton Heath FC back in the day, was formed in North West England. The year saw the FA stipulate the time for all football matches under its governance to 90 minutes. It proved to be a defining ruling in the history of the game.

Fast forward 50 odd years, and the first ever World Cup final to witness Extra Time had been won by the Italians, a team inspired by the first generation of Italian “Oriundi”, Luis Monti and Raimundo Orsi. Half a decade later, however, the game was pushed to the background, as indeed was everything else as World War II dawned large. The fight for the Jules Rimet Trophy resumed in 1950, as the Selecao were beaten by the Uruguayans in the infamous “Maracanazo”.

Two years later and thousands of miles away, Partizan Belgrade went on to reach the finals of the Marshal Tito Yugoslav Cup after a novel ruling, along the lines of the modern day penalty shootout. However, the new innovation was only sporadically used until the fairness of the existing rules came under scrutiny after Italy’s win over USSR in the 1968 Euros. With the scores staying level after 120 minutes and the accepted practice of the replay being unfeasible, only one solution was in hand – the mother of all anti-climaxes, the dreaded coin toss.

Everybody didn’t take too lightly to the practice of tossing coins or drawing the lots to decide the winner though. After watching his beloved national team bow out at the quarterfinals of the 1968 Olympics at Mexico City on a coin-toss, Israeli Yosef Dagan proposed a petition to the Israeli FA explaining a new concept known as the penalty shootout. Alternate stories resurfaced on the eve of the 2006 World Cup, however, as former DfB referee Karl Wald claimed that it was his brainchild, and he first presented it to the Bavarian FA. Irrespective of the quandaries over its origins, the ultimate football lottery was born.

The next few years saw the shootout become subject to all forms of praise and flak. However, its popularity went through the roof as some of the biggest contests on the planet were decided by a kick of the ball. The 1976 Euro final witnessed one of the most iconic moments of the game, as a certain Czechoslovakian player won his team the shootout against West Germany (who would’ve ever thought the Germans could lose a penalty shootout?) with a moment of absolute ingenuity. The man was Antonin Panenka. The name is enough.

The Germans weren’t to be denied for long though, as they prevailed over Les Blues in the first ever World Cup shootout in the 1982 semifinals, a match known more for Harald Schumacher’s horrendous tackle on Patrick Battiston, because of which the latter slipped into a coma.

A plethora of famous incidents from the spot happened over the following years – Liverpool’s Bruce Grobbelaar’s spaghetti legs against Roma in the 1984 European Cup finals. Jerzy Dudek’s famous reprisal of the same on that famous night in Istanbul. John Terry’s slip in the 2008 Champions League final. Tim Krul’s moment in the sun against Costa Rica. England’s never ending hoodoo. Die Mannschaft’s equally predictable dominance. Even the naysayers would agree on one thing: the game would be poorer without the shootout.

Experiments continued

A year before Baggio’s gut wrenching miss, FIFA introduced the Golden Goal rule, a practice prevalent at the time in the FA Cup under the name “Sudden Death”. The rule was simple. Whoever scored the first goal in extra time would win the match, thus reducing the chances of a shootout significantly. However, the rule became more hated than the shootout itself, as teams started playing thirty minutes of “park the bus” with the fear of failure ruling their thought process. However, it stood the test of time, as UEFA adopted it as the primary tie-breaking system.

In an incredible twist of fate, the first high profile match to witness a golden goal was again in the Euros. And it featured two rechristened foes of the past, Germany and Czech Republic again. And when Oliver Bierhoff tucked home the winner in extra time, the entire nation rejoiced. Germany had turned the table, after a tenuous wait of 20 years. Football had come a full circle.

Golden Goal was done away with six years later as FIFA introduced another short-lived concept, the Silver Goal. The rule stated that in case a team scored during the first half of extra time, the opposition would be given time until the end of the half, when the game would end unless they equalized. Needless to say, it fared worse than its predecessor with criticism pouring in from all quarters. Czech Republic were yet again, the first ever protagonists of the rule, as they lost out to Greece in the semi-finals of Euro 2004, sending the likes of Pavel Nedved and Jan Koller into tears.

With both experiments being done away with for good, football stands the winner. For what would the game be without moments like Anton Ferdinand’s miss in the 2006 FA Cup final, the “Gol di Grosso” that broke a million German hearts two months later, Sebastian Abreu’s Panenka that knocked Ghana out, Didier Drogba’s farewell penalty, Mario Gotze’s finish past Sergio Romero at the Maracana, one could go on and on and on.

Epilogue

It was the 9th of July, 2006. Another day, another World Cup final. The match was all about one man; such was his form, such was his aura. With extra time running out fast, pundits and fans alike looked at him to provide the moment that would change the match. For, he was the game changer. A few seconds later however, everything had turned on its head. Or rather, on his head. The whole world watched in shock as Marco Materazzi fell to the ground in a heap – Zinedine Zidane had just become football’s ultimate tragic hero.

For with Materazzi’s fall, fell the hopes of an entire nation – albeit that of the team he played against. Les Blues looked directionless without their dismissed captain, their talisman. As Fabio Grosso scored the winning penalty and gave joy to an entire nation that was reeling under the Calciopoli, one man looked on with a beaming smile. Finally, Roberto Baggio was a happy man. Catharsis was his.