Stopping diving in football - FIFA's losing battle

The date is July 2, 2010. The place is Johannesburg, South Africa. The event is the FIFA World Cup quarter final between Uruguay and Ghana.

On this most famous of footballing days, Luis Suarez began his long journey towards infamy, deliberately handling the ball on the goal line to keep Asamoah Gyan from winning the game for Ghana. Suarez was sent off, but Gyan missed the ensuing penalty and after a dramatic penalty shoot-out Uruguay progressed and Ghana were sent home.

If he was given a second chance, do you think that Suarez would do it again? Do you think he would suffer the wrath of the media and the shame of a red card to keep his country in a World Cup?

Of course he would. In fact, most players in the world would gladly offer that sacrifice for their team or their country in such a situation. Why? Because it is worth the risk.

That isn’t necessarily a slight on football players. For the most part, professional players are ethical people who have no desire to cheat in order to win. Ethics, however, are almost always put aside when the game is on the line, and often not by choice. In the heat of the moment, all a player is thinking about is winning.

This is why some players will always have a tendency to dive in a football match. No matter what their beliefs are off the field, if they see a challenge coming and they believe if they go down it might award their team with a penalty or get the opposing player sent off, they will take it.

Because it is worth the risk.

Creating the deterrent

As current FIFA rules stand, a player will receive a yellow card if he is seen by the referee to be simulating. Think about how woefully inadequate that is. Most dives come in the penalty area, conducted by forwards who believe they might be awarded a penalty for their deception.

With that in mind, let’s approach this as a gambling venture. If a player puts down a yellow card on the table, and for his wager there is a decent chance he will win a goal for his team, and perhaps the sending off of his opponent, would he make that bet? Every. Single. Time.

The only way to stop a player from diving is to bring about such serious consequences that the fear of those consequences overrides the impulsive need to do anything to win the game at hand. In other words, you have to make diving not worth the risk in the mind of a footballer. To do that, he has to be forced to wager much more than a yellow card. The question is; how much more?

The city-state of Singapore is a great example of how to instigate an effective deterrent. Singapore has one of the lowest drug conviction rates in the entire world. Why? Because a number of drug offences carry the death penalty, and those that don’t carry long prison sentences.

These are extreme reactions to problems, and most people are surprised when they learn of the harsh punishments in store for offenders. However, what cannot be argued is that the measures work; drugs are rare on Singapore’s streets. (Please note that I am not in any way condoning the use of the death penalty, I am simply using it to accentuate a point).

Underwhelming solutions

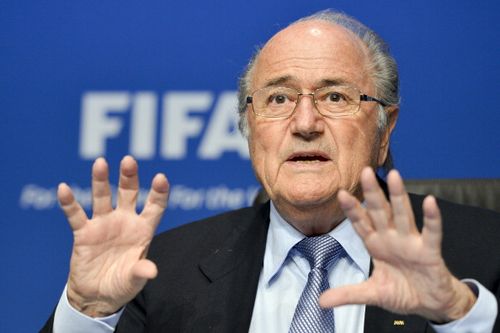

That is exactly why FIFA President Sepp Blatter’s new proposal won’t work. The head of world football’s governing body took to a weekly FIFA column in early January to propose the use of a time penalty as a deterrent to simulation of injury in football:

FIFA president Sepp Blatter

“I find it deeply irritating, when the half-dead player comes back to life as soon as they have left the pitch,” said Blatter. “The referee can make the player wait until the numerical disadvantage has had an effect on the game… In practical terms, this is a time penalty and it could cause play-actors to rethink. The touchline appears to have acquired powers of revival which even leading medical specialists cannot explain.”

Blatter’s proposal is well intentioned, but it could never be an effective solution to prevent diving. To start with, it would take a very brave referee to rule that a player wasn’t really injured in a challenge. Secondly, it is simply not a strong enough incentive to prevent play-acting.

The Daily Mail’s Neil Ashton goes a step further than the FIFA President. He recommends the use of the sin bin to eradicate diving.

Ashton was motivated by a dive by Oscar during Chelsea’s 3-0 victory over Southampton on New Year’s Day. The Brazilian, faced with a one on one opportunity with Saints keeper Kelvin Davis, threw himself to the ground to try and win a penalty. He was booked by referee Martin Atkinson, but went on to claim the man of the match award with a goal and two assists.

Obviously justice was not served that day. The yellow card did nothing to disadvantage Chelsea in any way, and they went on to make Southampton suffer for it. For Ashton, the answer was clear. He wrote “Let’s put cheats in the cooler for 10 minutes. Had Oscar been on the side-lines following his outrageous leap in the 55th minute, he would not have been on the field to make the telling contribution for the opening goal scored by Fernando Torres five minutes later.”

The value of the sin bin

Ashton’s solution is not a bad idea. The shame and exposure of a time penalty in a sin bin might just be enough to deter a player from diving in the future. However, perhaps even that does not go far enough.

To put a player in the sin bin for a few minutes is a proportional response to the problem of diving, but a proportional response won’t stop players. You only have to look at the use of the bin in other sports to know this.

Sin binning still happens regularly in sports such as Rugby and Ice Hockey, failing to stop players from committing infractions when they feel it is worth it or that they could possibly get away with it. It would be the same in football; unless you play centre half, 10 minutes in a sin bin is worth potentially winning a penalty.

What’s more, what if the dive came in the final minutes of the game? Would the threat of sitting out the final seconds really discourage a player from trying to win a late penalty? Probably not.

The sin bin is used as a penalty in sports such as rugby union and ice hockey

So what other solution are there? Former Premier League referee Dermot Gallagher leans a different way when troubleshooting the problem. Gallagher, who was a FIFA listed referee for eight years, told the BBC: “I think most people in this country would adhere to retrospective action. For me, I think an ex-referee, an ex-manager and an ex-member of PFA could look at video evidence and if all three agree on a dive, it’s a three match ban.”

Ashton and Gallagher have good concepts, but both have their flaws. A player in a cup final, for instance, would dive with little concern to a three match ban enforced in the following season. A ten minute sin bin, on the other hand, is of little consequence at the end of a game.