The legend of Catenaccio and Herrera's Inter Milan

Karl Rappan once saw a dream. In his dream, the opposition striker went past his central defender in the W-M formation, and thus had a clean run on goal. To counter this problem, he decided to put an extra body between his centre-back and the goalkeeper, who would thus stop and clear any chances that threatened his goal. This ideology of Rappan led to the development of ‘Verrou’ and more importantly, the Libero. This tactic was first used in the 1938 World Cup, when he was in charge of the Swiss national team. The system did turn out to be successful as the Swiss knocked Germany out of the tournament.

The idea travelled from Switzerland to Italy, where it was adopted by Nereo Rocco. This was a pivotal step in the birth of Catenaccio (which means door-bolt in Italian). The Cattenacio style of playing, as Trappationi says, “rules out defeat as far as possible.”

“The brutal defensive show on display, will repel all the romantics of the game, and will give rise to a devil: Anti – Football.”

Herrera’s Inter – A symbol of Calcio:

The 1967 European Cup final was probably the biggest clash of ideologies. On one hand, there was Helenio Herrera’s Inter, who had built a fortress on the pillars of defense, and on the other hand were Jock Stein’s Celtic, who went on an all-out attack with their wingers. And as the Tifosi gathered in Lisbon, they probably witnessed the fall of a kingdom. Celtic defeated Inter and went on to lift the European Cup, as Herrera and his kingdom turned into ashes, but not before winning back-to-back European Cups and stamping a legacy of their own. A legacy, called Catenaccio.

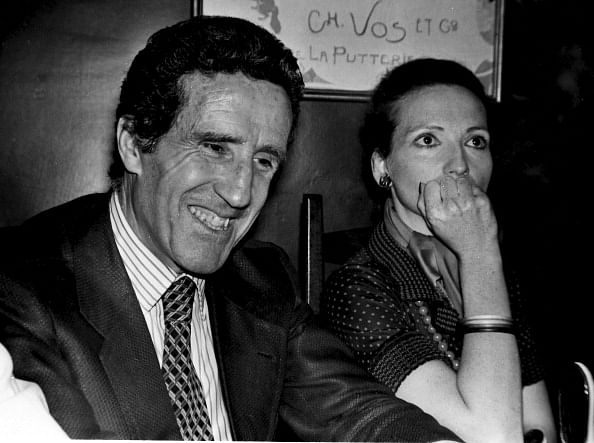

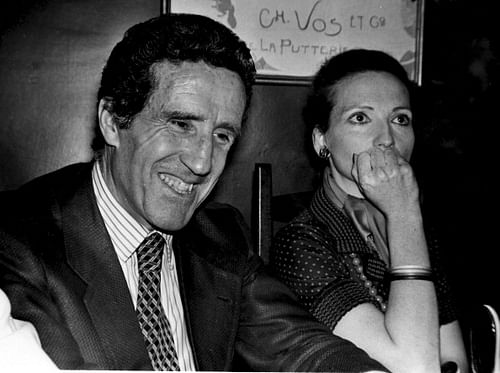

Herrera’s date with Inter rolls back to the start of the 60s, when the Argentine arrived at the San Siro with playmaker Luis Suarez, from Barcelona. Post his appointment, he embarked upon a journey to change the way Inter played football.

The system :

Herrera’s Inter

The world Catenaccio literally translates to a ‘door-bolt.’ As mentioned above, the Catenaccio way of playing football puts an emphasis on building a brick wall in front of goal and resorting to swift counter-attacks when the opposition overload their attacking numbers. The adjacent board depicts the system used by Herrera at Inter.

Armando Picchi, who played as the last line of defense, formed the backbone of Herrera’s Inter. As Kenneth Wolstenholme wrote in The Pros:

“If a player got beyond the line of four backs, either by dribbling his way there or by creating space with one-two passing movement with a colleague, he would be confronted by Picchi. Any player who ran through to pick up a long pass would be confronted by … Picchi. Any high lob or centre which was floated into the Inter Milan goalmouth would be picked off by … Picchi.”

Words cannot describe the importance of the Italian sweeper to the success of Grande Inter. Along with the triumvirate of defenders ahead of him, Picchi formed an unmovable core in defense, so much so that games were considered to be as good as finished the moment Inter scored a goal.

The three defenders ahead of Picchi were just as important to Herrera’s success. Though he played on the right side of a three-man defense, alongside Guarneri and Facchetti, Burgnich wasn’t a typical full-back. He was often deployed with the role of man-marking the opposition’s best attacking player. And given his single-minded approach to defending, Burgnich was also a decent ball player, which was something of a novelty in those days. On the left, Giacinto Facchetti was narrating his own fairytale. Such was the talent of the elegant defender, that Herrera had no hesitation in handing him a senior debut at the mere age of 19. For a player standing at 1.88m and weighing 85 kgs, Facchetti’s pace, refined technique and skill-set were unerringly fantastic during those days.

At the time, defenders were restricted to their half of the pitch, with their roles limited to stopping their opposition numbers. Pacy counter-attacks, which made use of defenders as the ‘first forwards’, were not known back then. Facchetti was the first of this breed. A breed which we normally associate the modern fullback with.

Inter Milan centre-forward Pino Boninsegna leaps high over Lazio’s Giorgio Papadopulo during their match at the Olympic Stadium in Rome. On the left is Inter Milan’s Giacinto Facchetti.

The three-man midfield consisted of Luis Suarez, Mario Corso and Carlo Tagnin. While Tagnin was the all-out defensive midfielder, Luis Suarez was the deep-lying playmaker, and Sandro Mazzola was the attacking midfielder or the second striker. Tagnin’s career was marred by the use of performance-enhancing drugs, which ultimately led to his death in 2000. Nonetheless, he was an absolutely bedrock for them in midfield. Helenio Herrera gave the uncompromising midfielder the main task of marking the opponent’s number 10, and thus playing the foil to the creativity of Suárez and Corso. His most memorable contribution was in the final of the European Cup in 1964 against Real Madrid, in which he was deployed to man-mark Alfredo Di Stefano. The Spanish legend was shackled for large parts of the game as Inter went onto win the European Cup.

In contrast to his style of play at Barcelona, where he was deployed as a goal-scoring midfielder, Luis Suarez changed his game to suit the needs of his manager at Inter. He focused his game on orchestrating play from the deep and was the lifeline of most of his side’s attacks and counter-attacks. If power, size and strength were not related to the diminutive Mazzola, determination certainly was. An attacking midfielder/inside-right with a lovely touch and vision, Mazzola saw the picture quicker than anyone else, and then made the most out of any attacking opportunity for his side.

On the right, the Brazilian Jair constantly rampaged down the flank. Primarily known for his crossing, Jair was also a decent dribbler of the ball, and was very quick on his feet. Mario Corso, who, unlike Jair, was given the luxury to cut infield, played on the left. The attack of Grande Inter was led by Aurelio Milani, who was the joint top scorer in the 1961-62 Serie A campaign.

The fall of Catenaccio:

Jimmy Johnstone of Celtic (L) and Tarcisio Burgnich of Inter Milan (R).

The defeat against Jock Stein’s Celtic signalled the beginning of the end for Catenaccio. Celtic had an astounding 40 shots on goal that night, as they overturned a one-goal deficit to win the European Cup. Even the Argentine innovator congratulated Celtic, saying:

“I congratulate Celtic, this is a great victory for them… but this is also a great victory for football.”

And then came Cruyff and his Ajax team, who would again mould the way football was looked at. Positional discipline, rigidity and the emphasis on defense were soon to be forgotten, as fluidity, positional interchange and a sole focus on attack came to the fore. Catenaccio was defeated by ‘total football’.

The spirit of Catenaccio died on the night of the 1972 European Cup final, when Cruyff demolished a hapless Inter led by Giancio Facchetti. The Nerazzurri defended desperately as the ‘total footballer’ ran rings around the once-formidable backline.

The legend of Catenaccio remains one of the most enduring legacies of Calcio till date. Through desperation, killing the spirit of football or resorting to the ugly side of the beautiful game, Catenaccio brought a plethora of success by making the teams using it effective winning machines. Inter won 4 Scudettos and back-to-back European Cups by building their fort around the pillars of Catenaccio. More recently, Greece shocked the world by winning the 2004 Euros, with their backbone providing the platform for a shock.

Not beautiful, yet effective and successful – that’s what makes Catenaccio one of the talked about legends of the beautiful game.