The UEFA Champions League needs more excitement and this is what can be done

Over the course of the UEFA Champions League group stage this season, we have witnessed some outstanding clashes, closely contested, of great quality and, above all, featuring some breathtaking football. Real Madrid vs Juventus, Barcelona vs AC Milan and the Group F games between Arsenal, Borussia Dortmund and Napoli were fixtures of a rich history, rare class and generated great interest the world over.

We also saw some ridiculously one-sided fixtures, such as Bayern Munich vs Viktoria Plzen or Paris Saint Germain vs Anderlecht, which ended with 6-0 and 6-1 scorelines over two legs. These mismatches did nothing for the competition except to allow the big boys to have their fill of cheap goals and hasten their qualification to the knockout rounds. If we were to search for positives, we could say that these games also gave the minnows their moment in the limelight and a healthy injection of cash, but that would be clutching at straws.

Games such as Bayern Munich vs Viktoria Plzen belie the status of the Champions League as the highest level of footballing competition

Games belonging to the former category used to be the norm in the glory days of the European Cup and the UEFA Cup. Games of the latter variety have sadly become far too common in the group stages of the Champions League in recent years.

Meanwhile, the Europa League has continued to introduce us to unknown clubs and their football. Or rather, it has simply remained a footnote to the big matches on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and we’ve largely only checked on the scores the day after, rather than catching the games live. The Europa League has been subjected to some stepmotherly treatment off late, with almost twice the number of games crammed into a single Thursday. Moreover, clubs have started to look at it as something of an unnecessary burden and a strain on their resources in the quest to reach the Champions League.

Why have things come to this stage at the top level of European football? To get to the bottom of this, a brief history lesson on the various major European club competitions and their formats is called for.

European club football history

The European Cup, the precursor to the Champions League, began in 1955 as a two-legged knock-out competition. Only the champions from each domestic league were allowed into this elite competition, while the league runners-up and subsequent finishers competed in the erstwhile UEFA Cup, which started in 1971 and is now rebranded as the Europa League. A third cup competition was the UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup, which was played as a straight knock-out by the domestic cup winners from 1960 onwards until 1999, when it was absorbed into the UEFA Cup.

The European Cup remained a knockout competition until 1992, when the quarterfinals and semifinals were replaced by a group stage consisting of two groups of four. The following year, it was rebranded the UEFA Champions League as television rights started to make a significant impact on the sport and slowly transform its finances.

In the days of the great AC Milan side of the late 1980s, the European Cup was played as a knock-out cup competition

In 1994, the tournament started to take shape as we know it, with a group stage at the round of 16 level, i.e. four groups of four. From 1997, league runners-up from the top ranked nations were added and the group stage expanded to six groups.

In 1999, entry was granted to even more clubs, four each from the top three nations and three apiece from the next three, and the number of groups increased to eight. Qualification rules have largely remained similar since then. Additionally, a second group stage with four groups of four, was added on in place of the Round of 16, to result in a bloated-up format with huge fixture pile-up. The second group stage was abandoned in 2003, and the format has remained untouched since.

Meanwhile, in the mid-noughties, the UEFA Cup, for the first time, shed its knock-out structure to adopt a rather ungainly eight-groups-of-five league stage. Since its rebranding as the Europa League in 2009, the number of competing clubs has been increased and the current twelve groups of four structure has been used.

The problem

Coming back to the issue at hand, the problem can be broken down into three major parts. Firstly, the Champions League needs to be rid of the one-sided contests, to make it worthy of its status as the very pinnacle of the game. Second, the Europa League’s former prestige needs to be restored, and it simply needs to attract more eyeballs. Finally, all of this has to be achieved without compromising on the number of clubs competing in Europe. In fact, UEFA President Michel Platini’s objective is to further increase the number of clubs involved in Europe.

The Champions League and the Europa League have gone from being out-and-out knockout competitions to the league plus knockout structure. With the huge matchday and television revenues generated by the large number of group stage fixtures, it’s safe to say going back to the knock-out format to generate excitement is simply not going to happen. Whatever must be done, must be done within the current framework, with room for only a little bit of tinkering.

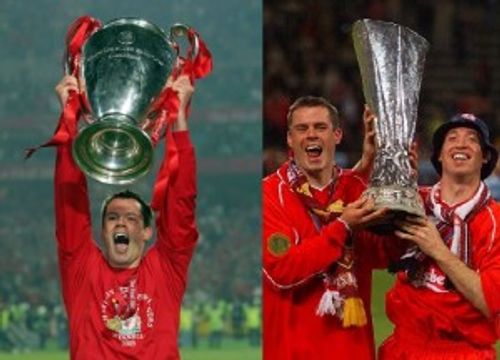

Having said that, the answer can be found within the very history of these competitions that we’ve briefly revisited. And who better to provide it than someone who has played in and won both the competitions and experienced firsthand UEFA’s tinkering of the formats over the past decade-and-a-half. Step forward, Jamie Carragher.

The solution

Jamie Carragher knows a thing or two about playing and winning at the top level of European football

In his column in the Daily Mail, he reveals that his best experiences in the Champions League came during the 2001-02 season in the second of the two group stages. Four groups consisting of four of the top clubs on the continent obviously adds up to really closely contested, hard-fought, exciting games, each game meaning something and critical to progress in the competitions. Quite simply, imagine each group to be the equivalent of the Arsenal, Dortmund, Napoli and Marseille group of this season. Sounds tasty? You bet!

Now two group stages is obviously unfeasible due to the huge fixture congestion it would cause. Therefore, the tweak Carragher suggests is simple – retain the 32 teams, but play a knockout round to whittle them down to 16 and then play the group stage. Seeding the draw for the first knockout round would ensure no two ‘big’ sides are drawn against each other that early into the competition.

The Carragher argument would at once make sure that both the competitiveness as well as significance of each group game is lifted. It would make the big sides play a big must-win game right at the start, meaning no one has any guarantees simply by finishing in the Champions League positions domestically. It also gives the minnows a great chance to make a big impact, for surely a knock-out game gives them a much bigger opportunity to progress than a 6-game league stage.

The teams dropping out at this knock-out level could then compete in a playoff for the Europa League. This would simultaneously raise the level of competition in the Champions League and add glamour to the Europa League with the presence of bigger sides in the group stages and consequently increase the global interest in the competition.

Quite by happy accident, this structural rejig also resolves that sticky issue of the teams placed third in Champions League groups dropping into the Europa knock-outs. It is an arrangement that is downright disrespectful to the teams grinding it out in the Europa League groups, and rightly will have to be discontinued to implement the suggested changes. To additionally improve the standing of the Europa League, the participation money could be redistributed more equitably and the calendar rejigged to give it prime midweek slots in weeks that don’t have Champions League football, although all of this is easier said than done.

In short, the proposal would increase the exclusivity of the Champions League, give the Europa League a much-needed gloss without compromising on the total number of clubs in Europe. Which means, it meets all the objectives outlined earlier.

In a sense, the resultant landscape would resemble the old European Cup, a highly exclusive competition inhabited only by the league champions, and the UEFA Cup, with a number of exciting, ambitious clubs. While the European Cup remained the highest prize in European club football, interestingly it was the UEFA Cup that produced some of the most memorable football, for a larger number of quality teams participated in it. If Carragher’s suggestion can do the same for the Europa League, it would have more than served its purpose.

Finally, to actually execute such changes, a thousand logistical issues need to be resolved, all stakeholders brought on board and the finer details hammered out. But that is par for the course, as far as the UEFA is concerned, since it has been reworking its club competitions endlessly over the last two decades. If the Carragher argument does indeed achieve all that it promises to, we might just be in store for some deliciously exciting European club football for decades to come.