Wallsend Boys Club: England's most impressive football factory

Former Newcastle and England captain, Alan Shearer is Wallsend Boys Club’s most famous product. (Getty Images)

If you want to find a top quality young player in England, you might think to look at Manchester United‘s Youth Academy, where many of the North West’s finest players have been groomed over the years. David Beckham, Paul Scholes, Ryan Giggs, Gary and Phil Neville all learned their trade there, as did many greats from previous generations, such as George Best, Mark Hughes, Sir Bobby Charlton, Nobby Stiles and Duncan Edwards.

Better yet, you might want to consider West Ham’s ‘Academy of Football’, which has an honours list even more impressive than Manchester United. Rio Ferdinand, Michael Carrick, Joe Cole, Jermaine Defoe, Frank Lampard, Glen Johnson, James Tomkins, Freddie Sears, Mark Noble and Anton Ferdinand all refined their skills with the Hammers, as did World Cup winners Geoff Hurst and Bobby Moore back in the glory days of English Football.

(L-R): Frank Lampard, Rio Ferdinand, Michael Carrick. Just three of the many quality footballers to have emerged from West Ham’s famous academy. Carrick however, learned the fundamentals of his game in Tyneside, playing at Wallsend Boys Club. (Getty Images)

There is, however, another champion of youth football on England’s shores, one that does not quite garner the attention of the more glamorous aforementioned academies. This particular football factory is not an academy of one of England’s biggest football clubs. Far from it. It does not have huge, breath-taking facilities and near-limitless funds. For most of its existence it has run matches and practices on whatever patches of council-owned grass it can find. Its coaches are all volunteers and as a charity its finances are dependent on contributions from outside sources. Yet despite all this, it has grown to be one of the premier producers of professional footballers in the entire country.

It is Wallsend Boys Club.

Based in North Tyneside, just a few miles away from Newcastle United’s St James’ Park, Wallsend Boys Club has been coaching youth football for local boys since the 1970s. The club began in 1907 as a multi-purpose sports club set up to provide the young people in the area an opportunity to engage in recreational activities such as snooker, table tennis and judo. Football wasn’t given any special attention at the club until 1975, when a separate sub-committee was created to oversee the football programme.

Once football became the club’s primary focus, an extraordinary talent for unearthing future football stars was found. Overall, the club has produced over 65 players that have gone on to play professional football, many of them in the top divisions. Despite operating on a shoestring budget, Wallsend boasts a roll of honour that most academies would envy. Here is a list of some of the more recognisable players who once donned Wallsend’s now famous green jerseys:

| Wallsend Boys Club Roll of Honour | Clubs played for |

| Peter Beadsley | Newcastle, Liverpool, Everton, Bolton, England |

| Steve Bruce | Norwich, Manchester United |

| Alan Shearer | Southampton, Blackburn, Newcastle, England |

| Michael Carrick | West Ham, Tottenham, Manchester United, England |

| Lee Clark | Newcastle, Sunderland, Fulham |

| Robbie Elliot | Newcastle, Bolton |

| Brian Laws | Burnley, Huddersfield, Middlesbrough, Nottm Forest |

| Neil McDonald | Newcastle, Everton, Oldham, Preston |

| Eric Steele | Newcastle, Brighton, Peterborough, Watford, Derby |

| Alan Thompson | Newcastle, Aston Villa, Celtic, Leeds United |

| Steve Watson | Newcastle, Aston Villa, Everton, Sheffield Wed |

| Tony Sealy | QPR, Crystal Palace |

| Ray Hankin | Burnley, Leeds United, Peterborough |

The main football facility for the club until 2011 was a dreary looking building located in Wallsend’s Station Road. There, in the confined space of a 5-a-side court that the kids nicknamed the “sweatbox”, players were able to refine their talents at a young age, focusing on key fundamentals like accuracy of passing, ball control and close dribbling skills.

Peter Beardsley, who earned 59 caps for England and was a star of the English First Division with Liverpool and later Newcastle, played in the “sweatbox” up to 5 nights a week as a boy, and considers that experience key to his eventual success. He told The Telegraph:

“While in the ‘sweatbox’ you learned how to think more quickly on your feet. The tackles would come flying in and if you were kicked it was probably because you’d held on to the ball too long, so you had to be quick and nimble in possession, but how quickly you could get the ball back was also vital.”

“The Sweatbox” – Wallsend Boys Club’s Station Road facility, where many future stars learned the game.

Even now that Wallsend Boys Club conducts most of its football operations in a brand new £1.2M outdoor facility, the principles behind what they teach the young players hasn’t changed. The voluntary coaches at the club don’t focus on controlling or supressing the natural flair of young prodigies; instead, they encourage it. Adventurous play is at the forefront of Wallsend’s coaching philosophy.

Club President Peter Kirkley, who has been with the club for over 40 years, shared with The Telegraph what he sees when he goes to academies across the country: “I go to academy matches and all I hear from the coaches is ’pass, pass, pass’. I long to hear someone say: go on son, take him on.

He has a point. Most academies now are producing players who seem nervous to keep hold of the ball for more than 5 seconds. Players are taught how not to lose games rather than how to win them, and individual flair and ambitious play are quickly coached out of the kids. This pessimistic approach to coaching is why a lot of players in the English leagues now play more like Gareth Barry than Gareth Bale.

That of course, is a big problem for both the excitement and quality of the game on the British Isles, and the FA is clearly concerned about it. Trevor Brooking, the FA’s Director of Football Development, admitted recently that “I certainly think technically we’ve fallen behind a lot of countries such as Spain, France and Holland“.

That’s stating the obvious. It is no secret that emerging English talent lacks the technical proficiency and flair of their European counterparts. While players on the continent are being nurtured to fit into technically demanding systems such as those run at Barcelona and Bayern Munich, players in England are being nurtured to play for Stoke. The very top teams in the EPL are therefore ignoring England’s youth systems and look to the continent to find the most gifted players.

Arsenal is a perfect example of this. Their system has been famous for two reasons over the past couple of decades. Firstly, they have been widely regarded as the most technically sound team in the Premier League. They play beautiful football, keeping the ball on the ground and playing in short, quick triangles that require incredible precision and skill.

Secondly, they hardly ever field English players.

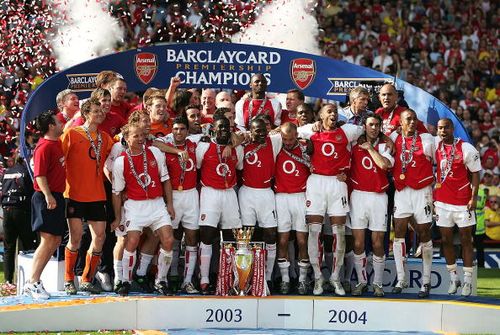

That is not a coincidence. Arsene Wenger has not been able to find the players in England who are technically capable of fitting into his system, with the exception of Jack Wilshere and Theo Walcott in recent years. The “Invincibles” team of the 2003-2004 season swept teams away with their skill, but they did it largely with Robert Pires, Patrick Vieira, Freddy Ljungberg, Gilberto Silva, Edu, Dennis Bergkamp and Thierry Henry. Three Frenchmen, two Brazilians, a Swede and a Dutchman.

Arsenal’s “Invincibles” of 2003-2004: Arsenal have been renowned for using foreign players in their highly successful system. In this championship winning season, Arsenal’s only English midfielder was Ray Parlour, who played largely in a backup role to captain Patrick Vieira. (Getty Images)

The problem exists as much now as it did in 2004. In today’s game, one of the most important positions is “in-the hole”; the player that can drop into space behind the forwards and act as the catalyst for the team’s attacking play. More and more teams are utilising this role in order to improve their creativity going forward. However, the players filling these roles are not English.

In fact, most of them are Spanish. The Iberian state has cornered the market on “in-the-hole”players in recent times. Juan Mata plays the position for the European champions, Chelsea. Manchester City employ a number of players to fulfil the role, but most frequently it is David Silva. Santi Cazorla was brought to Arsenal in 2012 for that exact purpose. The same can be said for Swansea’s acquisition of Michu, although he has since been moved into a more conventional striker’s role.

England does not produce “in-the-hole” players. They lack something necessary for the position, whether it be the flair, the smarts, the ball control or the passing accuracy required. Whatever it takes to be successful in this role, English players, as a generalisation, do not have it. The most likely explanation for this is that they just aren’t taught it.

Perhaps if more academies took the approach that Wallsend do, things would be a little different in English football today, not just with “in-the-hole” players but with the quality of talent being produced in every position.

In the same interview with The Telegraph, Wallsend’s President Peter Kirkly said “our priority has never been to create professional players. The idea has always been to give local lads and lasses a game of football, help them grow to love the sport.” They should be applauded for their approach. The optimistic style of coaching retains some sense of excitement to the game we all love, as they encourage creative freedom as well as sound fundamentals. Because they are not an academy, and are not primarily interested in producing professional footballers, they can concentrate on making sure young players are enjoying the game when they play it. That is a key part of successfully developing young talent that is often lost behind everything else; the kids have to be enjoying what they are doing.

The FA have their own techniques for improving the number of quality players emerging from our country’s youth systems. In considering how the development of youths can be improved in English football, Trevor Brooking said that “We need to improve facilities such as changing facilities, certainly the pitches…”

Is this right though? Wallsend Boys Club stands to show otherwise. The Station Road “Sweatbox” was little more than a dull square brick box on the side of the road, so poorly constructed that high winds in 2011 caused the entire back wall to fall down. That didn’t stop them being one of the most successful developers of youth football in the country. Poor facilities are not a restriction on an institution’s ability to nurture talent, that much is clear.

The back wall of the “Sweatbox” after high winds caused major damage to the back wall.

So if a charity run by volunteers on a run-down estate in Tyneside can produce Alan Shearer, Michael Carrick and Peter Beardsley with nothing more than a ball and a rundown indoor 5-a-side pitch, there is no reason why the country’s academies can’t do even better. But they don’t. Are academies so focused on being in control of a player’s development that they suppress an individual’s unique creativity? Is the vanilla coaching style that teaches players only how to play safe football killing their love of the game? Is football in England too boring?

The story of Wallsend Boys Club perhaps answers those questions for us.