How traditions and science come together to make marathon champions

To break the two-hour marathon barrier, a runner would need to beat the fastest marathon that’s ever been clocked — 2:02:57 — by about 3 percent. That means he’d need to shave seven seconds off each of the race's 26.2 miles. To most, it’s a seemingly impossible challenge. But to Nike, it’s a goal worth chasing down.

The athletes brave enough to accept Nike’s invite to attempt to run a sub-two-hour race are Eliud Kipchoge, Lelisa Desisa and Zersenay Tadese. Months of testing and analysing data on a stable of the world’s best distance runners determined that these three would be physically primed for the challenge. But much of the intention to partner with them boiled down to the simple fact that they’re naturally better than other runners at running fast for a long time.

Their years of experience and expertise give them a unique advantage, which is a big reason why the Breaking2 team of coaches and scientists understood that optimizing rather than radically changing their daily training and fueling strategies was the best way to approach its attempt to lead the athletes to what it hopes will be the biggest victory in distance running to date.

The athletes and their coaches have played an integral role in defining the training programs that have gotten them to where they are today. Dr. Brad Wilkins, a physiologist and the director of Nike Explore Team Generation Research in the Nike Sport Research Lab, and Dr. Brett Kirby, researcher and lead physiologist of the Nike Sport Research Lab, were brought on to oversee the day-to-day science behind Breaking2.

“As elite athletes, they have incredible, well-established training programs that are working,” says Wilkins. “Our goal has been to work with the runners and their coaches to provide analysis and feedback.” Here’s why this coming together of worlds has the potential to make the sub-two-hour-marathon dream a reality.

Ways experience has determined what works

Training plans evolve as the athlete does

Kipchoge’s weekly plan has variety and specificity, and progressively builds throughout the program. He’ll do two-a-days, long runs, speed work around a track and Fartlek workouts (Swedish for speed play) each week. “Eliud is very in tune with his body, so he often lets his response and perceived exertion dictate his pace,” says Kirby.

Meanwhile Desisa’s initial focus was generally endurance, where he did a lot of long, easy-to-moderate foundational runs. He added in more specific track workouts to build his speed and intensity later in the program. Tadese’s strategy is almost the opposite of Lelisa’s: The first half of his training was speed heavy to help him become familiar with race pace, whereas later his goal has been to lengthen out the duration of his speed with endurance so that he can maintain that pace over time, says Kirby.

Warm-ups are (mostly) simple

All of the athletes do a typical shuffle-jog (sometimes so slowly that they almost drag their feet along from what looks like a standstill, describes Kirby), progressively increasing their pace for about 30 minutes.

Desisa and his crew also do a more “ritualistic” pre-run routine made up of dynamic movements that lasts for about 30 minutes. “It looks like a dance,” says Kirby.

Teamwork is paramount, but so are solo runs

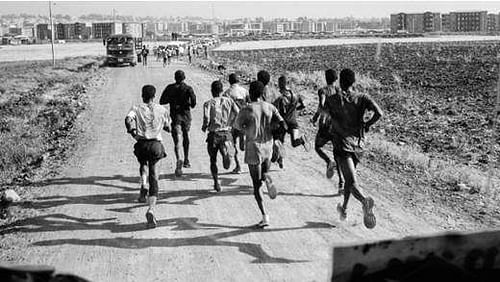

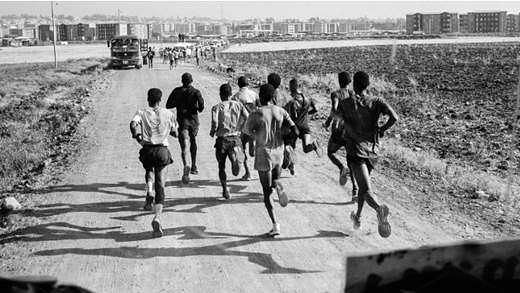

Generally, the athletes run with others for motivation and comradery. Desisa has his own crew of six to eight guys that are there to support him however he needs it. On long runs, Kipchoge runs among a big group made up of up to 60 locals, pro runners or coaches. But if they’re targeting a very specific workout, they may run alone or with a couple of others. “Zersenay does many of his runs on his own,” says Kirby.

Sleep keeps them at the top of their game

None of the athletes do what would generally be considered a standard cool down. The most critical part of their training routines — typical of athletes running more than 100 miles a week — is recovery.

“Zersenay is known as the sleeping man because when he’s not running he’s sleeping,” says Kirby. When Desisa isn’t training, he’s relaxing. Kipchoge spends a lot of his down time balancing rest with daily life in his camp. “Besides napping and enjoying tea with his teammates, he also does chores, such as pull water from his well or work on the camps grounds,” says Kirby.

Most rest one day a week or as needed. Some of the guys get massages up to three times a week typically after their hardest training sessions.

Running is everything

They don’t lift weights. Or do yoga. They just run. “To run fast you need to run,” says Wilkins. Though all very different, each athlete’s training program is constantly evolving and adapting to adjust to proficiencies and inefficiencies. “Generally, runners at this elite level aren’t flexible,” says Wilkins.

Contrary to what some may think, the research suggests that less flexibility tends to correlate to better performance. “The theory is that stiffer legs lose less energy,” explains Wilkins. (He relates it to a stiff spring, which stores and releases much more energy than a looser one.)

Day-to-day diets are loose

At this elite level, the runners already know what foods fuel their daily runs best, though Wilkins and Kirby do suggest the runners eat meals that are about 50-75 percent carbohydrate, 20-30 percent protein and the remainder whatever they want. Also, the scientists provided specific guidance for post-training nutrition intake.

For example, they highlighted the importance of immediate ingestion of protein and carbohydrate following harder training sessions, and in some instances where the athletes don’t have quick access to full meals, they guided them to intake a recovery beverage.

Where Science evolves tradition

Key metrics inform how to progress each run

Since embarking on this mission, Wilkins and Kirby have visited the runners multiple times, where they did in-depth assessments to obtain information on important markers, including V02 max, how much fluid they lose while running, how much energy their muscles store and so on.

When they aren’t with the athletes they maintain contact through regular phone or video conferencing sessions. During their training runs, the athletes wear GPS watches with a heart rate monitor (with an accompanying chest-strap transmitter). After each run, the coaches and scientists analyse the data together to understand and interpret the athletes’ performance and progress. They use the info they gather to consult with the runners’ coaches to constantly evolve their plans.

They believe in the altitude advantage

All three athletes live and do most of their running at altitude. Kipchoge’s camp is in Kenya, Desisa’s is in Ethiopia and Tadese splits time between Eritrea (where he lives) and Spain (where his coach lives). “Because there is less available oxygen at altitude, over time the number of red blood cells can increase, enabling your blood to carry and deliver more oxygen to your muscles,” explains Wilkins.

“And the more oxygen your muscles have the better they function, which can help you to run farther, faster.” The higher concentration of red blood cells can remain for up to two weeks after a person leaves altitude, so the supposition is that the blood cell boost provides a competitive edge at sea level.

Race fuel is individualised and precise

The scientists are focused on offsetting fluid losses from sweating and maximising energy levels. This narrows their focus to the 48 hours leading up to the race and 24 hours after hard training sessions in two key areas: type and delivery method, and individual need.

“We’ve created a custom carbohydrate mixture for each athlete based on data we’ve gathered over the training program that indicates how much fluid they lose while running and how much their guts can absorb,” explains Kirby. Beyond that, they each have different types of carbohydrates, amounts, fluids and flavours.

Frequency of fueling is specific

Through analysing data on each athlete and extensive trial and error, the Breaking2 team has determined the runners’ ideal time to consume fuel during the race: at every 2.4K (each loop of the track they’ll run around, the Autodromo Nazionale Monza complex outside Milan, Italy).

“So about every seven minutes the athletes will intake their specific mixture that keeps them hydrated and energised,” says Kirby. This is all new to the athletes, say the scientists, because previously each runner was consuming less than 60 grams of carbohydrates per hour have had to familiarize themselves with ingesting a greater quantity of carbs at race pace.

Wilkins, Kirby, and everyone else on the Breaking2 team continue to use all this information and experience to evolve Kipchoge’s, Desisa’s and Tadese’s strategies. “We’ve been collecting data since we started, and we continue to learn a ton from the athletes to get us in the best place possible for race day,” says Wilkins. “Most runners don’t have this level of personalization and access to this kind of testing and coaching.” When you combine that with each athlete’s sheer mental toughness, you have the potential to reach the unknown.

“No matter what we do from a science perspective, these guys have to run 26.2 miles at 13.1 miles an hour,” says Wilkins. “That is amazing.”