Andy Murray's magical dance of darkness

Andy Murray has been given a lot of free, mostly unsolicited advice in his career. ‘Be more aggressive’. ‘Take the initiative in baseline rallies’. ‘Aim for the corners with your forehand’. ‘Hit your second serve with pace and depth instead of rolling it in’. ‘Stop whining and get on with it already!’ These suggestions were seemingly put forth to help Murray make his big breakthrough and end Great Britain’s storied 76-year Slam drought. But Murray did all of those things and still ended up on the losing side at Wimbledon this year. What changed yesterday, in the US Open final against Novak Djokovic? A bit of magic. A bit of dark, brooding magic, to be more precise.

Throughout his career, Murray has excelled in one area more than any other: outsmarting the opponent in a series of cat-and-mouse games. It’s one of the disadvantages, if you will, of being outrageously gifted; you have so many options at your disposal that you feel tempted to manipulate and trick your way out of a match rather than go the mundane, blast-and-bruise route. Murray is a master at lulling opponents into his web of deceit; there’s no other player on tour who can get a match played on his terms as subtly, or effectively, as Murray does. In his semifinal against Tomas Berdych, Murray massaged the ball, putting it teasingly within Berdych’s grasp, but with constantly changing pace and spin; the big gusts of wind swirling around Arthur Ashe stadium made sure that Berdych could only watch in agony as his attempts to generate pace out of Murray’s tantalizing mid-court shots went sailing past the sidelines. Yesterday, Murray did something similar, but none of us expected Djokovic, winner of the last 3 hardcourt Slams, to fall into the trap as easily as Berdych did. That’s the magic of magic though, isn’t it? It turns expectations upside-down. Or even inside-out, you might say.

Inside-out. The inside-out forehand, one of the most important shots in men’s tennis today, has always been Murray’s Achilles’ heel. He’s never been much of a pace-setter with the shot, and his inability to put away the mid-court ball with a swatted forehand winner was frequently chalked up as the reason Murray hadn’t won a Slam before yesterday. He didn’t exactly show us a dramatically improved inside-out forehand yesterday. What he did do, though, was hit it with enough spin and depth to elicit a string of slice backhands from Djokovic. Slice backhands? Djokovic? Yes, you heard that right. Playing right into Murray’s strategy, Djokovic started the match playing at half-speed, refusing to take big cuts at the ball in order to accommodate the swirling winds that had made a return to Arthur Ashe after a one-day vacation. The first set slightly resembled a practice session; the average speed of the groundstrokes from both men was considerably lower than what we’re normally accustomed to seeing in the final of a Grand Slam, and neither player seemed willing to go on the offense. Predictably, this worked in Murray’s favor, as his shots (which weren’t aimed for the lines) were either carried by the wind away from Djokovic, or opposed by the wind, making them fall short and out of the Serb’s comfort zone. In contrast, Djokovic’s deeper drives regularly missed the mark, sometimes falling a couple of feet long or wide. Murray used the conditions expertly, effectively neutralizing Djokovic’s devastating two-handed backhand by mixing up his crosscourt and inside-out forehands and repeatedly tugging Djokovic from one corner of the baseline to the other. It helped, of course, that Djokovic’s timing, thrown haywire as it was by the wind, was probably the worst I’ve seen from him in the last three years.

The Serb’s timing issues continued into the second set, and by the middle of it he was making such ghastly errors that it made us want to look away from the TV screen. But after going up by two breaks and building a 4-0 lead, it was Murray’s turn to disintegrate, as he lost his game completely to allow Djokovic to draw even. Djokovic wasn’t done with his bouts of sub-standard play yet, though, and serving at 5-6, he produced a bunch of errors to gift Murray the break and the set. Murray had a two-set lead after 2 hours of mostly uninspired tennis, and the match never really recovered after that.

The Serb’s timing issues continued into the second set, and by the middle of it he was making such ghastly errors that it made us want to look away from the TV screen. But after going up by two breaks and building a 4-0 lead, it was Murray’s turn to disintegrate, as he lost his game completely to allow Djokovic to draw even. Djokovic wasn’t done with his bouts of sub-standard play yet, though, and serving at 5-6, he produced a bunch of errors to gift Murray the break and the set. Murray had a two-set lead after 2 hours of mostly uninspired tennis, and the match never really recovered after that.

The scoreline and duration of a match are often considered as measures of its quality. In that respect, both the scoreline and duration (4 hours 53 minutes) of the final are extremely flattering to the level of play in the contest. Both players kept peppering random, inexplicable errors for the majority of the match, and neither player seemed to want to take control of the proceedings. Armed with a 2 set-lead and the prospect of ending his agonizing Slam wait, Murray went into a shell and pretty much tanked the next two sets. He looked like he was being tortured on the court, at one point even screaming ‘Jelly!’ to himself, apparently because his legs were moving as if they were made of jelly. Don’t ask me how the minds of these pros work. Djokovic, meanwhile, had fallen into a trench at the start of the third set from which there was seemingly no coming back. His back against the wall, all hope seemed lost. In short, Djokovic had reached the stage where he could start hitting out and play his most spectacular tennis of the night. In true Djokovic-style, the Serb came back from the dead, and started yanking an increasingly foul-mouthed Murray all over the court. Djokovic may be developing a dangerous pattern here: he can’t rely on his shot-making skills to rescue him from the brink of defeat every single time. For a viewer, though, this habit of Djokovic’s makes for some fine theater. Visions of his semifinal classics against Federer from the last couple of years briefly appeared before our eyes, and the start of the fifth set seemed the perfect time to bring out the popcorn and sit back for some good old-fashioned bloodshed.

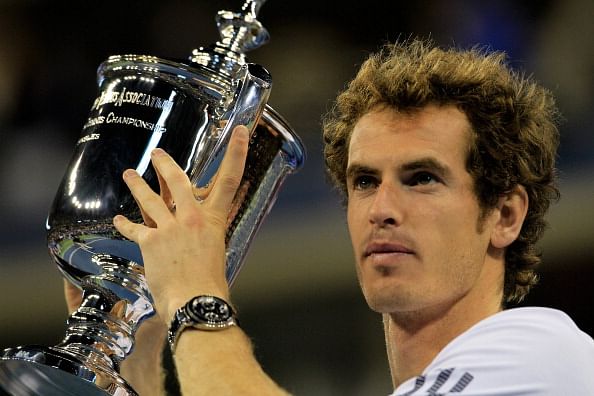

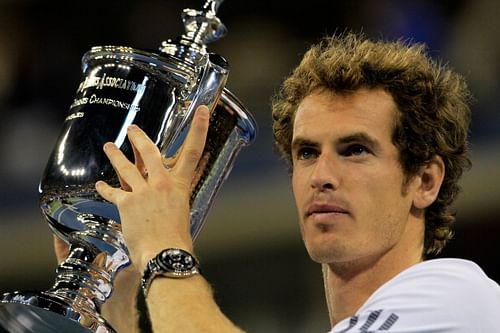

As it turned out, Murray was the only one who would raise his game in the last set. With his big lead having disappeared, the Scot freed himself to play his most persuasive tennis, and a fatigued Djokovic couldn’t keep up. There was a medical timeout just before the finish too, as if to make sure that the night ended on a justifiably anti-climactic note. Fittingly, the match ended on a Djokovic error, and Murray, perhaps setting a new trend of inexpressiveness after a marathon victory, looked around in his inimitably deadpan fashion, his face a mixture of mild relief and disbelief. Great Britain’s 76-year drought had finally been ended, and Murray was a Grand Slam champion. It took a few minutes for that to register fully in our minds; it only sank in completely when the camera flashed to Judy Murray and Kim Sears hugging and weeping profusely.

Was this victory the big breakthrough moment that Murray truly deserved? On one hand, this was a mediocre match; maybe we’ve been spoiled by the dramatic thrillers we’ve been treated to in Slam finals recently, but 31 winners against 56 errors for the victor (and a similarly poor 40 winners to 65 errors for Djokovic) aren’t exactly indications of a high-quality, gut-wrenching battle. On the other hand, the conditions were decidedly tricky throughout the encounter – Djokovic struggled mightily with his timing, and Murray’s slice backhand was shockingly out of tune too – so the high error count is perhaps not that inexplicable after all.

Where Murray did shine through was in the small adjustments that he made to counter Djokovic’s ball-striking superiority. He used his forehand wisely, as I said earlier; relying on depth and direction more than pace, he repeatedly got the better of the forehand-to-forehand exchanges. He got first serves in on the the big points, even if they were a bit slower and spinnier than his normal flat serves; by making clever variations in his first serve, he elicited just enough return errors from Djokovic to win those rare but crucial free points. He defended brilliantly, as he has done throughout his career, even if he displayed a mortal fear of the net despite being in position to finish a point with a volley on several occasions. But with Djokovic prone to pulling the trigger a little earlier than usual, that didn’t matter; Murray stayed in the points just long enough to goad several misfired kill shots out of the Serb. Most importantly, however, Murray completely outplayed Djokovic in the one area that they both like to pride themselves on: the return of serve. The Scot put almost every strong first serve from Djokovic back in play, and made him pay dearly for missing the first serve: Djokovic won only 42% of his second serves all match, and that number would have been even lower if it hadn’t been for Murray’s lackadaisical play in the third and fourth sets. Djokovic rightly has the reputation for being the most aggressive, fearsome returner in the world, but yesterday Murray showed that his play-the-percentages strategy on the return of serve is almost as effective as hitting clean winners off it.

Murray’s sly, counterpunching playing style may have its share of critics. His on-court demeanor, with regular outbursts against himself, his support group and sometimes even his shoes or racquet, may ensure that he’ll never have the legions of fans that Federer or Nadal do. And his perpetually deadpan, almost morose countenance may never endear him to the media. But in the span of two weeks, Murray has validated all of these seemingly negative attributes; a Slam victory can set so many things right for a tennis player that you’d be forgiven for thinking it is the Elixir of Life itself for these pros. With the US Open in his bag, Murray has proven that his intelligent, varied game has a place in the sport today: spectators will learn to live with, and maybe eventually even come to love, the way in which Murray uses his unique bag of tricks to toy with his opponents. His tantrums and shenanigans when things aren’t going his way may be a permanent part of him that no amount of drills with Ivan Lendl can drive out; but if he can win a Slam looking and feeling like a defeatist, who can fault him? And I don’t know about you, but the expressionless face that he puts on in his public appearances is a bit of a refreshing change from the emotionally high-strung trio of Federer, Nadal and Djokovic.

Murray’s sly, counterpunching playing style may have its share of critics. His on-court demeanor, with regular outbursts against himself, his support group and sometimes even his shoes or racquet, may ensure that he’ll never have the legions of fans that Federer or Nadal do. And his perpetually deadpan, almost morose countenance may never endear him to the media. But in the span of two weeks, Murray has validated all of these seemingly negative attributes; a Slam victory can set so many things right for a tennis player that you’d be forgiven for thinking it is the Elixir of Life itself for these pros. With the US Open in his bag, Murray has proven that his intelligent, varied game has a place in the sport today: spectators will learn to live with, and maybe eventually even come to love, the way in which Murray uses his unique bag of tricks to toy with his opponents. His tantrums and shenanigans when things aren’t going his way may be a permanent part of him that no amount of drills with Ivan Lendl can drive out; but if he can win a Slam looking and feeling like a defeatist, who can fault him? And I don’t know about you, but the expressionless face that he puts on in his public appearances is a bit of a refreshing change from the emotionally high-strung trio of Federer, Nadal and Djokovic.

Andy Murray might not be the champion that everyone wants, but that’s what makes him so special. He is different from other champions. He’s not powerful on the court or likable off it, but he can make both his opponents and the spectators play on his terms. There’s a darkness within Murray, a darkness that is starkly and disturbingly visible during his frequent outbursts. Rather than fall into the abyss of that darkness, though, Murray uses it to manipulate his way out of trouble. And ever so often, he even uses his scheming methods to put on a tennis show of such preposterously impossible gimmicks that it makes our jaws drop in disbelief.

Isn’t that precisely what magicians do?