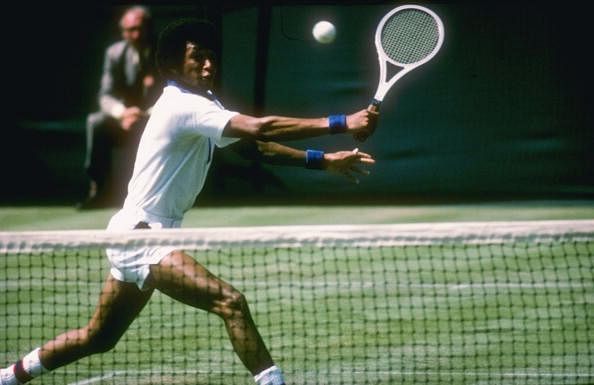

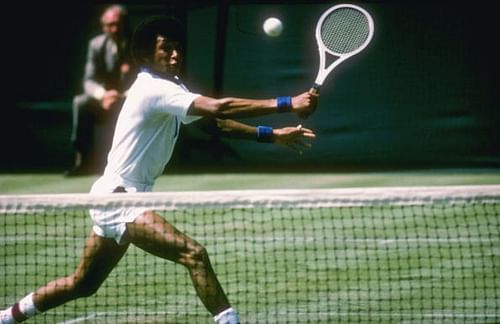

Arthur Ashe - The man who brought colour to Wimbledon

If the world of film-making ever has to pick a script for a blockbuster tennis film, the build-up to the 1975 Wimbledon Final is a made-to-order topic for the big screen.

Look at it like this.

Jimmy Connors was a superstar. He was America’s golden boy. Brash, handsome and armed with a backhand capable of carving out winners at will, Connors was known for his controversial style of play and his mean court-side sneer. Ashe, on the other hand, was the first player of African American origin who had scaled the ladder of international tennis. He was unshakable on court, had a game that was highly erratic and was backed by a cult following. Ashe had been involved just a few months back in stomping Connors out of the French Open in a controversial ban, which was backed by the ATP.

Connors was known to the world then as a bit of a sell-out. He’d follow the path of the dollar and thrived on exhibition matches. Just around that time, he signed a contract with World Team Tennis (WTT) for becoming a part of the Baltimore Banners. French officials opposed this entry because Connors kept his monetary interests at heart, paving the way for a huge number of scheduling conflicts. WTT players were banned at Roland Garros till 1978, which spoiled Connors’ chance at completing a Grand Slam in 1974, as he had swept up the remaining three.

Though Connors’ lawsuits against the ATP had been withdrawn by the time Wimbledon-75’ rolled around, his 2 million dollar suit against Ashe was still standing. His comments about how Ashe’s mob of fans reminded him of Harlem had gone viral too, and not in a good way. Centre court was bursting with raw energy. The atmosphere in the stadium was something no one had imagined would steam up at SW19 in 50 years.

To top all this, Connors had been on one of his destructive streaks en route to the final. He had demolished players left, right and centre to set up a final no one thought Ashe would win.But Ashe defeated Connors in one of the best tactical matches in tennis ever. Connors, who thrived on taking the ball early, was completely caught off guard by Ashe’s pulp mix of lobs, slices and slow drives. It was more of a chess match than a tennis contest. Ashe won 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4 and stamped himself in the history books as the only ever African-American winner of Wimbledon since. He also remains the only African-American to have won the Australian Open and US Open.

Though Ashe’s three Grand Slam titles seems a small number for a player to be considered among the greatest of all time, the conditions through which Ashe fought to become a tennis player were hard. He was forced into mandatory army training, where he honed his skills as a player as well as achieved the fitness he was known for in the end.

In ’79, Ashe suffered a heart attack, which shocked the public considering he was one of the fittest athletes in the world. He contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion later in his life, which he had while fighting toxaplasmosis. He was forced to go public because of a story published in a magazine called ‘USA Today’. He spent the rest of his life trying to educate people about AIDS as well as heart disease.

Ashe was one of the greatest celebrity-turned-humanitarians that ever existed. He was arrested for protesting against apartheid twice in the 80s. He worked to clear up the misconception that only homosexuals or people using IV needles can get AIDS. A few years before his death, he founded the Arthur Ashe Institute of healthcare, an initiative that earned him Sports Illustrated’s ‘Athlete of the year award’.

Ashe achieved a lot, on and off court. His memoirs, ‘Days of Grace’ are a must read for any tennis fan. The fact that the USTA named Centre Court at Flushing Meadows the ‘Arthur Ashe Arena’ is testimony to the larger-than-life personality he was and will always be remembered as.