Australian Open 2010: Why Roger Federer Is, Well, Roger Federer

The way Roger Federer continues to chug along the path to immortality and beyond, merrily adding Grand Slam titles to his résumé, free of any kind of injury or opposition, you get the feeling that the best chance of his domination ending any time soon is a premature retirement caused by him hurting himself when he falls to his knees in celebration. When a player falls to his knees and weeps tears of joy after winning a Grand Slam for the 4th time to add to the record 15 he’s already captured at 4 different venues, you know you’re dealing with a person who doesn’t have a limit to the well of emotion within him. How is it possible for a man to be so happy at achieving something that he’s done so many times that it’s become almost irrelevant now? Half the world stopped caring about the number of Slam titles that Federer would win for the rest of his career the moment he crossed Pete Sampras’s tally of 14 at last year’s Wimbledon. Ironically, the only time that I can remember when Federer DIDN’T cry after winning a Slam was after Wimbledon last year. He’s a weird bloke, that Federer. Almost inhuman (no, 23 straight Grand Slam semifinals is not going to prompt me to remove the ‘almost’ from that sentence).

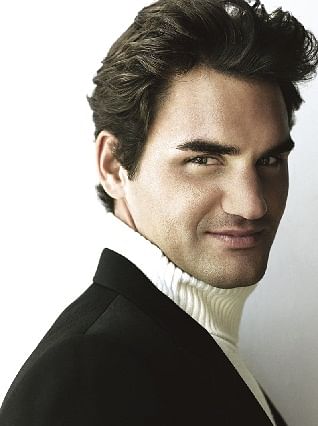

roger federer by mario testino vogue 2006 2

People can talk about Federer’s artistry and his quickness and his precision and his power and his deft touch, but the real secret behind the man’s unnatural run of successes may be something that he puts on show after every one of those triumphs – his emotions. When a heartbroken Andy Murray nearly broke down in tears in his podium speech, Federer said that “it is nice” to see a player crying like that after a loss because it shows how much he cares about winning. There’s a very fine line between mocking arrogance and heartfelt sympathy, isn’t there? A statement like that may be construed by some to be a gloating slap in the face of Murray, and by some others to be a clever justification for Federer’s own infamous show of emotion after losing to Rafael Nadal last year. To me, however, it spoke of Federer’s perfect understanding of the spirit that drives the efforts of every single athlete on this planet. I don’t know whether such a simple statement would have had a greater effect in making the loser of the day feel better about himself than did Nadal’s iconic arm-around-the-shoulders and sympathetic smile that got so much acclaim last year. I do know one thing, though: Federer cares so much about winning that not only does he not mind a few tears here and there after a loss, he actually WELCOMES them.

I’ve always felt that Federer’s greatest accomplishment may be something that most casual tennis watchers don’t even know about and probably never will. When Federer was a teenager (and a very prodigious one at that), he was thought to be the second coming of compatriot Martina Hingis (although he won a lot less than the saucy Ms Hingis), throwing tearful tantrums after losing any match and smashing racquets with alarming regularity. There were fears in tennis circles that he would always be hugely temperamental and that he would never do justice to his spectacular talent, despite his now-legendary defeat of Pete Sampras in the Wimbledon tournament of 2001. But then, sometime around 2002, something changed: some claim it was because of the tragic death of his long-time coach, while others say it was out of the realization that he would never get anywhere with his temperamental ways, but Federer was no longer the irritable, spoilt kid that he once was. He put on a mask of stoicism during his matches that was so unshakeable it was reminiscent of Bjorn Borg. He showed no happiness at winning point after splendid point and no anger at making the wildest of shanks. How does a John McEnroe turn into a Bjorn Borg?

His calm on-court demeanor only helped him keep his head during his matches, enabling him to adopt better shot selection and be patient and focused during entire rallies, games, sets and matches. I need hardly mention what happened after that: 22 Major finals out of 27 since Wimbledon 2003, with 16 of those ending in triumphs, is not something to be sneezed at. Is it even humanly possible to keep your emotions so firmly locked for the entire duration of a tournament that you look almost robotic to the outside world? Surely there must be a release somewhere? And then we wonder why he must force those weeping sessions on us and spoil our otherwise perfectly cheerful viewing experience.

Federer is passionate about the game of tennis to a degree that we ordinary humans would never be able to attain, much less comprehend. It’s his love for the sport that makes him so danged good at it; it’s that simple. Sure, the man is supremely gifted – some of the shots that he hits look almost ethereal, and his footwork and movement around the court (most particularly his flying forehand) look positively magical. But then, Marat Safin, bless his heart, was supremely gifted too. You don’t see 16 Grand Slam titles stamped against his name, do you? Earlier, when I heard Federer repeatedly say in his interviews that he would continue playing till the age of 35 if his body cooperated, I used to doubt the sincerity of his words. I’m not saying I’ve become a believer now, but I sure as hell am no longer as rigidly cynical about it any longer. Records are important to him, just like they are to everyone else, but playing good tennis and competing on the highest levels are so much more important to him that the two aren’t even comparable. And while that may sound all so very poetic and rosy from where we’re watching, the fear that such an attitude can, and should, inspire among his fellow tennis players would be anything but poetic or rosy.

Andy Murray, however, is one player who would do well to inject some measure of confidence into himself along with that fear, because he clearly does have the game to challenge Federer, if not on a consistent basis, then at least on occasion. What happened yesterday was caused partly by Federer’s jaw-dropping brilliance and partly by Murray’s big stage jitters. When you’re armed with a distinctly attackable second serve, you don’t serve at 57% in a Grand Slam final against Roger Federer. You just don’t. Not unless – a) you are Rafael Nadal, or b) you want to be given a first-class beat-down. The fact that Murray somehow managed to avoid the beat-down (it was a straight sets affair, I know, but it was a very tight straight sets affair) speaks volumes about his immense talent. The man’s going to win a Slam one day; all he needs to hope for is to face someone in the final who doesn’t care as much about the game as he himself does. In other words, anyone other than Roger Federer. And the way that Federer is going right now, that opportunity may not come for another 7 years (Federer has 7 years to go before he turns 35, right?). Can the whole of Britain wait another 7 years? What is 7 years, anyway, when you’ve waited a hundred and fifty thousand?