Can Roger Federer defeat Father Time again, for one last dance?

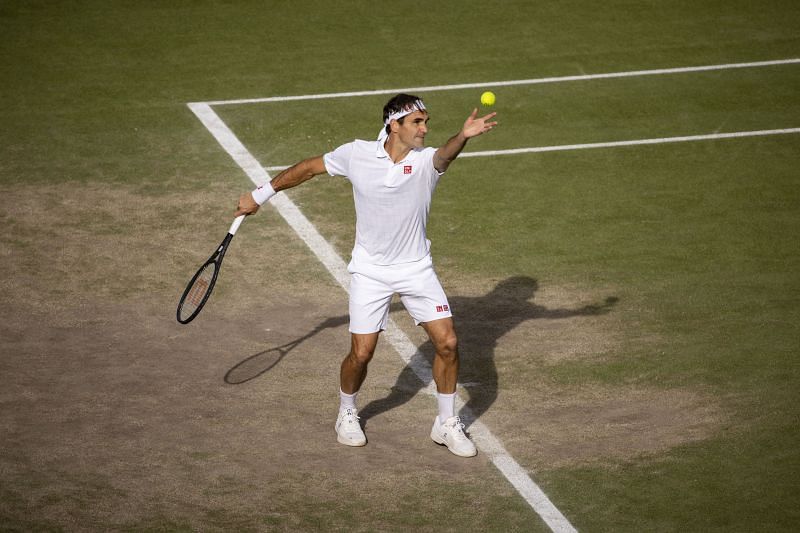

On a balmy summer's day in July, Hubert Hurkacz disrobed the emperor. He even fed the great Roger Federer a bagel on his own Wimbledon court.

But now it turns out the emperor may already have been limping on a leg that day, fighting Father Time just as much as he was battling a rival 15 years his junior. The 20-time Grand Slam champion announced last night that he would be undergoing another surgery to repair his right knee.

This will be the third procedure on the same knee since he went into the break after the 2020 Australian Open.

Roger Federer dropped the bomb on his Instagram feed, which prompted social media and news wires to go into a tizzy. As sudden as it may have felt though, it wasn’t an entirely unexpected development.

The Swiss has been recuperating at home since his quarterfinal loss to Hurkacz, withdrawing first from the Tokyo Olympics and then Toronto and Cincinnati.

"I just wanted to give you a bit of an update (sic) what’s been going on since Wimbledon," Federer said. "As you can imagine, it's not been simple. I've been doing a lot of checks with the doctors as well on my knee, getting all the information as I hurt myself further during the grass-court season and Wimbledon.

"That’s just not the way to go forward, so unfortunately, they told me for the medium to long term to feel better, I will need surgery. I decided to do it," he added.

The Basel native turned 40 last week, celebrating with his close friends and family. That also means the clock is ticking, and the clock tends to lack mercy or a mind.

It is indifferent to greatness, and becomes particularly harsh on the body with each passing season.

Roger Federer fighting age and aches

Knee surgeries are tricky even for people trying to lead a regular life, people who are just taking kids to school, getting to work and home. In the case of an athlete, it becomes doubly difficult; the various physiological markers that sustain speed, stamina and strength start tapering away after missing just two weeks of training.

Athletes such as Roger Federer train for hours together on their skills, agility, strength and endurance. As their training routine matures, they extend the regimen to fit in carefully calculated doses of pre-exhaustion work. That is an essential step in their dance on the edges of excellence.

Pre-exhaustion training helps their muscles and mind continue to function at a high level of performance despite teasing their limbs to the limit. Muscle strength and a strong aerobic base are not static rewards for the mind-numbing work put in by athletes.

According to physiologists, it takes just two to eight months of not exercising to send the body back to a state where it hadn’t experienced any exercise. That would be a frightening prospect for Roger Federer who has thrived for years on a dedicated regimen of planning and preparation, before peaking at specific times during the tennis calendar.

"I'll be on crutches for many weeks and also out of the game for many months, so it’s going to be difficult of course in some ways," Federer continued in his Instagram video. "But at the same time I know it's the right thing to do because I want to be healthy, I want to be running around later as well again and I want to give myself a glimmer of hope to return to the tour in some shape or form."

But returning to the tour, even if in some lesser "shape or form", would be far from easy. Roger Federer recently admitted that recovery is already taking longer. The painful process of cellular atrophy doesn't spare the great or care for their greatness.

It is in its character to destroy the greatest edifice, to eat into the bricks one small chip at a time. Despite Federer's nuanced effort to stretch the envelope, time has begun extracting its pounds of flesh.

Sports scientists agree that strength gains last longer than aerobic gains in a typical athlete. But lack of exercise for a couple of weeks to a month can result in loss of endurance, muscular strength, lean muscle mass and neuromuscular training adaptations.

The last of those means that muscles do not fire as they were normally trained to after a period of rest. In Roger Federer’s case, that might mean a forehand that lands in the net instead of sailing along safely to the deep end of the opposite side, or being a microsecond too late with the foot or racket to return a serve.

"I am realistic, don't get me wrong. I know how difficult it is at this age right now to do another surgery and try it," suggested an explicitly cautious Federer. "But I want to be healthy. I will go through the rehab process I think also with a goal while I’m still active, which I think is going to help me during this long period of time."

But as his muscles start to realize they don't need to store as much energy as they may have in the past, they would begin to hold lower levels of glycogen. That would lead to atrophy, shrinking the muscle fibers. And once the fibers shrink, they will need significantly more work to contract.

The recovery process could take far longer than at any time during Roger Federer’s career. As the Swiss' heart adapts to pumping lower volumes of blood into the body, the threshold at which he can train would be reduced; before long, his muscles would start begging him to stop.

"I'll be on crutches for many weeks and then also out of the game for many months," Federer warned.

As an elite athlete with an outstanding team of professionals, the 40-year-old would be fully aware of the time required for him to not just strain and load the knee, but also to restart high-performance training. That means his fans have no choice but to adapt to the new normal.

Most of them already understand that Federer's best is well behind him. But the romance of their relationship with him leaves them hoping he can still find it somewhere down the road, for a fortnight of high-octane tennis with men half his age.

Roger Federer himself would be wishing that he can arrive in London next year for a memorable cameo at Wimbledon, or maybe an emotional farewell in Basel. And if Federer can still defeat time and continue to layer his legacy on wobbly knees, he could well be considered Marius Petipa, the 20th century ballerino, in disguise.