The Rafa Reinvention: Can Nadal take a leaf out of Federer's book as he attempts to prolong his career?

If you wanted to pick a new-age trope to live your life by, you could do a lot worse than ‘40 is the new 30’. We see evidence of that idea everywhere – on advertising billboards, in organizational strategies, even in romantic relationships. And tennis, as a sport, has taken rather well to the slightly less marketable sibling of that motif – ‘30 is the new 20’. You have your Stan Wawrinkas winning Slams after going past 30, and your Ivo Karlovics producing their best tennis at 36. Never has age sounded more like just a number.

But if 30 is the new 20, why didn’t Rafael Nadal get the memo?

You’ve probably heard of the much-lamented fact that this week has been the first since June 2003 that both Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal are out of the top 4 in the ATP rankings. That’s a period of consistency and dominance lasting more than 13 years, but the ridiculousness of this stat is a discussion for another day.

So what ails Nadal, and how can he rediscover his lost mojo? Yes, I realize that Federer should be a part of this morose conversation too. But in comparison to Nadal, the Swiss is a lot older, considerably less fit and, before he was laid low by knee and back injuries this year, a little more proficient with his recent results.

The tragedy of Federer’s decline can be dealt with more effectively if he returns in 2017 and immediately puts in a string of poor performances. But for now, the more pressing concern is Nadal’s form and future in the game.

Since pulling out of the French Open ahead of his third round match, Nadal has been a rather ordinary 10-6 on the tour, with the low point coming in the form of a first-round loss to Victor Troicki at the Shanghai Masters this week. The defeat was so dispiriting that it prompted Nadal to declare that he wasn’t sure if he was going to see out the remainder of the season.

Time for alarm bells? That would have been the right question to ask if the bells hadn’t already been tolling faintly for the better part of the last three years. Nadal hasn’t reached a Slam semifinal since the 2014 French Open, and has actually made just two quarterfinals in that time – both of which ended in straight sets losses. He did win a Masters tournament earlier this year – in Monte Carlo – but his puzzling early Slam losses have been a hot topic of discussion in the tennis world for a while now.

The suggestions and advice have been flowing in thick and fast all this time. He should change his coach; he should stand closer to the baseline; he should become a serve-and-volleyer; he should alter his serving grip. The man himself, bless his heart, seems to have tried out every single thing except for the coach bit, but with little success.

Notably though, Nadal seems convinced that all his problems begin and end with the forehand. “I need to recover the forehand. I know I need to hit forehands,” he said after his loss to Troicki. “I need to move faster to hit more forehands. But I need to be more confident with the forehand to make that happen. Everything is a cycle.”

When your forehand has helped you win 14 Grand Slams and build a clay fortress more impregnable than Winterfell, you can’t be blamed for obsessing over that one shot. And by most accounts, Nadal’s forehand has been the cause of plenty of his misfortunes lately. The inside-out version in particular has broken down far more often than he’d have liked, the down-the-line screamer has become almost as rare as a Yeti sighting, and even the trusted crosscourt variant has become too spinny and safe.

But is it all really down to just that one shot? Will he recover all of his lost ground if he just flips the forehand switch? In other words, is the Nadal forehand actually a ‘magic’ shot, as it has been described so often in his career?

Like all hypothetical scenarios, it is impossible to accurately predict whether Nadal will be a force once again if he rediscovers the venom of his forehand. But with Nadal having turned 30 this year, and the miles on his body not getting any shorter, I wonder if he would be better served by accepting that his forehand is never going to be what it used to.

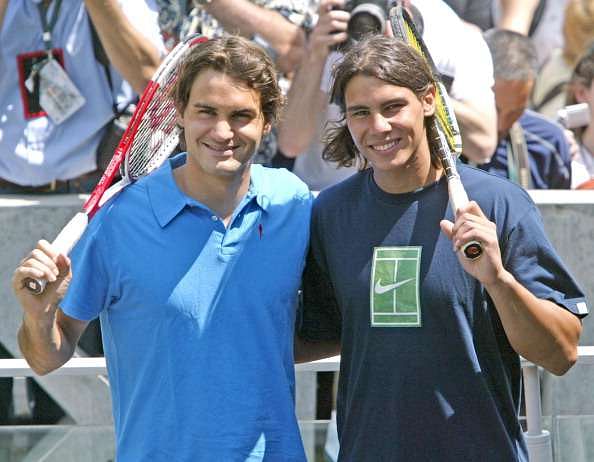

The parallels with long-time rival Federer are hard to ignore

Three years ago, Roger Federer was in a similar predicament to what Nadal finds himself in today. In fact, his situation was even worse, if that is even possible. The titles had dried up, the stranglehold over Wimbledon had been shattered for good, and even qualifying for the year-end championships seemed like an impossible task. But the Swiss somehow managed to crawl his way to the end of the season, which ended in a fashion that had become painfully familiar by then – with a loss to Nadal.

Except that even in familiarity, there was cause for consternation in the Federer universe. This was his first indoor loss to Nadal, signalling that there was no place for him to hide anymore. Every last bastion had been taken away from him, and that too with a certain jarring suddenness. If that didn’t shake things up in his camp, nothing would.

So in the off-season, the wounded tiger went to work. He brought on childhood idol Stefan Edberg as an additional coach, switched to a larger racquet, made some large-scale changes in his on-court strategy, and viola! he was back in the Grand Slam conversation. Yes, it’s that easy – if your name is Roger Federer.

Just kidding, of course. Nothing about Federer’s resurgence in 2014 was easy, even if it seemed so to us while watching from the cozy confines of our homes.

For a player wielding a 90-sq.in. racquet head all his career to switch to a 95-sq.in. is tremendously difficult; we already had evidence of that during Federer’s disastrous post-Wimbledon claycourt excursions in 2013, wherein he suffered losses to Daniel Brands and Federico Delbonis (no, I didn’t just make up those names). Moreover, when you’ve established a decade-long reign over the tour by playing from the baseline, a decision to suddenly re-incorporate serve-and-volley into your game would be enough to send an ordinary mortal into palpitations.

But Federer stuck to his guns, and he eventually made it all work because he had the right people around him to go with his considerably large skill-set. He may not have won a Major in 2014 and 2015, but he did reach three finals and came close to the No. 1 ranking, which is far more than what most tennis players in their 30s could ever hope to achieve. We probably don’t realize it now, but Federer’s resurgence in the last three years will one day make for a very awe-inspiring story.

The lessons for Nadal aren’t immediately discernible, but they are present alright

So what, if anything, can Nadal learn from Federer’s journey of rediscovery? It’s tough to draw an apples-to-apples comparison, because the games and mindsets of these two all-time greats are just so starkly different. We’ve all heard the ice-and-fire song, which has often been more gripping than George RR Martin’s version – lefty vs righty, attack vs defense, grass vs clay, passion vs composure. But amid all their differences, Federer and Nadal share one common, unmissable trait: they have the champion gene.

For Nadal, as it was with Federer, nothing less than giving his best on the court will ever do. And despite all his recent struggles, Nadal’s best – even his 2016 best – is enough to beat anyone not named Novak Djokovic or Andy Murray. So the first thing that he has to do, in my opinion at any rate, is to trust his game.

Sure, that probably reads like the most obvious product out of the stating-the-obvious factory. How could Nadal himself not thought of that? But it’s hard to dismiss the idea that while Nadal may have sworn to trust his game at all times, he hasn’t always remembered that simple formula on the court.

His toughest lows in recent times have come in tiebreakers or in deciding sets at Slams – against Fabio Fognini and Lucas Pouille at the last two US Open Championships, against Fernando Verdasco at the Australian Open, against Djokovic at Indian Wells, against Juan Martin del Potro at the Olympics, and even against Troicki in Shanghai earlier this week. In the most tense moments of the match, he starts looking visibly short on confidence, and starts hitting his forehand either too short or too long.

Effectively, two of Nadal’s greatest strengths – his mental toughness in crunch times, and his forehand – have become his biggest liabilities in the last two years. But while the forehand may not entirely be a confidence issue, the mental aspect certainly seems to be one. And no amount of toil on the practice courts can give you match confidence; that part of a player needs to be permanent.

But how can Nadal make that a permanent part of his repertoire again? By getting a new coach, of course. And I don’t mean firing Toni, who has by all accounts been the single biggest outside influence in Nadal becoming such a great champion.

I think the Spaniard needs to get a fresh pair of eyes on-board, even if those eyes are present in a secondary role. Federer got Edberg into his camp, but he always had Severin Luthi as his primary advisor. There’s no reason why Nadal won’t benefit from such a set-up too.

Toni is probably indispensable to his nephew’s presence in the sport; without him, Nadal would likely be lost. But if the King of Clay were to get someone to assist Toni, that new head might look at his game from a slightly different perspective, convincing him that there’s more than one way to win than just attacking the backhand with a hooked forehand.

It’s time to explore the hidden skills that Nadal almost surely has in abundance

The good thing about having the champion gene is that you are usually adept at a number of different aspects of the game. Against all odds, Nadal has learned to volley like a maestro; his recent doubles exploits readily attest to that. So who’s to say he can’t amp up his other skills to such an extent that they become borderline impossible to counter too?

He could start slicing his backhand more, a la Del Potro. He could start playing the drop shot liberally. Heck, he could even incorporate the SABR into his armoury. He could do anything he wanted to, if only he was made to realize that he could pull it off.

My point is that Nadal doesn’t need to fixate on any one of these tricks; he’s so naturally gifted, that he could try ALL of it and still come out successful. And he needs a new voice to drive home that point, because it’s unlikely to come from Toni.

Nadal also needs to focus on his biggest strength – which is not his forehand or mental toughness, but his foot speed. He may have slowed down a trifle in recent years, but he’s still faster than 99.99% of the tour; probably even 100%. Why does he need to go for the big, unreliable forehand in those tense tiebreakers and deciding sets? He can still wear down almost all of his opponents with his defense.

What is Federer’s biggest strength? Some would say it’s his serve, some would say it’s his forehand, some would say it’s his volley. I say it is the sum total of all these aspects – his offensive mindset. And from 2014 onwards that’s been the biggest change in his game – aside from attacking the net more, he’s also stopped slicing his backhand as much as he used to, and he’s used his bigger racquet head to impart more pace on his second serve. Federer and Edberg recognized that he’s not going to win matches with his defense any more, so they resolved to turn up the volume at the opposite end of the spectrum.

Can you imagine how scary an opponent Nadal would be if he did both of the above things – basically, developing a varied, multi-faceted game that had relentless running at its core? He’d be like Fabrice Santoro raised to infinity.

Scheduling, scheduling, scheduling

Another thing that Nadal can learn from Federer: better scheduling. Just last week I found out that the Spaniard has decided to drop the South American claycourt tournaments from his 2017 schedule, and instead play at Rotterdam in early February. And try as I might, I just couldn’t wrap my head around that decision.

Just why would he play an indoor hardcourt tournament – by far his worst surface – after the end of a hardcourt Slam?

Nadal is never going to be known as an indoor expert, and he’ll always be considered a claycourt colossus. So why not play as many claycourt tournaments as possible in the twilight years of his career? He likes playing on dirt, it’s easier on his body, and God knows he’s bloody good at it. If he decided to play only claycourt tournaments in the entire season, my guess is he’d still be in the top 10. And he’d certainly have a much better shot at adding to his Slam tally.

Federer didn’t make such a drastic change to his schedule, but he had decided to skip all the claycourt tune-ups this year before his knee surgery altered his plans. I don’t even know why Federer keeps playing the French Open; he’s thoroughly unlikely to ever win it again, and he’d be better served by focussing on his Wimbledon preparation in the months leading up to it. But at least the Swiss has taken cognizance of his late-career frailties, and made definitive tweaks to suit them.

Nadal will likely never again be the player that he was from 2005 to 2013, and nothing can ever make that reality less painful. But you can see from every match he plays, and every interview he gives, that the fire to give his best on the court is still burning brightly within him. And for a player as gifted as him, that fire, when fuelled in the right direction, is usually enough to produce consistently strong results.

There’s no foolproof blueprint by which Nadal can regain his mojo. But if he is ever short of ideas on how to get back into the winners’ circle, he’d do far worse than taking inspiration from his fellow GOAT contender.

It’d be an utter shame if Nadal didn’t come to personify the ‘30 is the new 20’ mantra the way so many other tennis players in recent times have. Maybe Federer could give him a call, now that he has so much time on his hands?