The genius of Pete Sampras

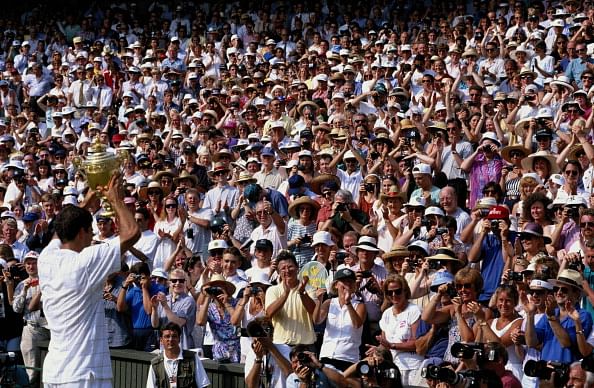

1995: This is when Pete Sampras officially took over the keys of the Centre Court from Boris Becker.

This article isn’t about how many slams Pete Sampras won. This article isn’t about what he did, on which court, against which opponent and on what surface. This article won’t talk about how many weeks he stayed on top of the game. These are known facts. Statistics aren’t enough to do justice to a man whose game moved tennis by leaps and bounds.

This article is simply about the beauty of his game, and how he was as a person.

Sampras decided to play tennis at a time where he invariably met all the other men he’d be compared with after his retirement. He fought the trio of Connors, Borg and McEnroe followed by Lendl in the eighties and early nineties. He battled his contemporary rivals which included the likes of Agassi, Courier, Ivanisevic, Rafter and Cash. He brushed rackets with the heroes of the early 2000s, which saw him face Safin, Hewitt, Moya, Ferrero and a young Federer.

When he left the game in 2002, he left mountains above the rest, with achievements that tennis would talk about for the rest of its future.

What gave the man the will to propel to the top of the game? He mentioned it in his autobiography. To quote the legend himself, “I was born to play tennis.”

Sampras followed the path of Bjorn Borg to develop a lethal combination of an icy demeanour on court and an equally brutal game to dominate tennis for almost two decades.

The best part of his game was that his was the most open game tennis had seen. Everyone knew his shots. Everyone knew what he was good at. Everyone knew where he was a bit weak.

He was so good that beating him despite this divine knowledge was close to impossible.

Sampras played all his strokes with one grip and one model of racket his entire life. He held a continental grip, which is perfect for serve and volleyers, but makes the baseline duelling popular in today’s topspin times slightly more tough.

He used a Wilson Pro Staff racket which weighed close to 400 grams and strung at a tension of 72. One must stress on the fact that the racket and tension are enough to render the forehand of a normal tennis player unconscious after a few rallies. Sampras’ forearm was the size of a minor cannon at the end of his career.

What made Sampras such a formidable foe was primarily his serve. He was among those few players who saw no merit in taking speed off the second serve.

Known particularly for serving aces during times of extreme pressure, Sampras was well renowned for his serve and volley combinations. He’d kick a second serve well out of reach, or chip and charge his way to the net to finish off a point. This is why he enjoyed so much success on grass and hard courts. He would play points that were quick and finish off service games within a trice.

His next most important weapons were his reach and forehand. Sampras would hurl himself at seemingly out-of-reach balls to hit running forehands which were the stuff of legend.

Superhumanly fit for an athlete of his generation, Sampras followed a strict diet and training routine, also famously sleeping for 13 hours a day. His annual treat of a cheeseburger after every Wimbledon was very famous as well.

His mentality on court was, in many ways, exactly like Borg’s or Federer’s. He was unflappable. But people made a grave error of judgement by calling him boring.

True tennis aficionados know Pete’s game was Joga Bonito. His game was beautiful in every sense possible. Even if one streams one of his old matches, the simplicity of the flat backhand and deep groundstrokes along with pure dominance at the net make watching him a treat for the eyes. He was so different from Andre Agassi, his fiercest rival, that Nike made millions filming advertisements featuring both of them. They pioneered the most cult Nike tennis advertisements of all time.

Pete Sampras eventually went on to be slightly more open with the public. His emotional match against Courier in Australia and playfulness at his recent exhibitions at Madison Square Garden have shown his lighter side.

Sampras turns 42 today. He will always be a hero to those born in the seventies and eighties, who grew up waiting for Wimbledon to start each year to see his heroics.

Maybe a day will come when he will agree to slide back into tennis once more, perhaps as a coach, or as an expert for a news channel. But no one will disagree that the day he makes his entrance once again, tennis will make way for a king that left his kingdom with his head raised high and no reason to look back, and his pockets full with 14 Majors, the highest any man had managed to collect till then.