Gimmick Some Lovin': Last Man Standing

In each edition of Gimmick Some Lovin', we take a look at one iteration of a gimmick match available on the WWE Network. Some are iconic for their success, others for the extent to which they flopped, and some just... happened.

We defined a "gimmick match" as, in any way, adding a rule/stipulation to or removing a rule from a match, changing the physical environment of a match, changing the conditions which define a "win", or in any way moving past the simple requirement of two men/women/teams whose contest must end via a single pinfall, submission, count out, or disqualification.

Because Tuesday, November 7th is the date when voters across the United States will participate in state and federal elections, we'll take a look at another WWE performer attempting to leverage his fame into a political career (because what's the worst that could happen there?).

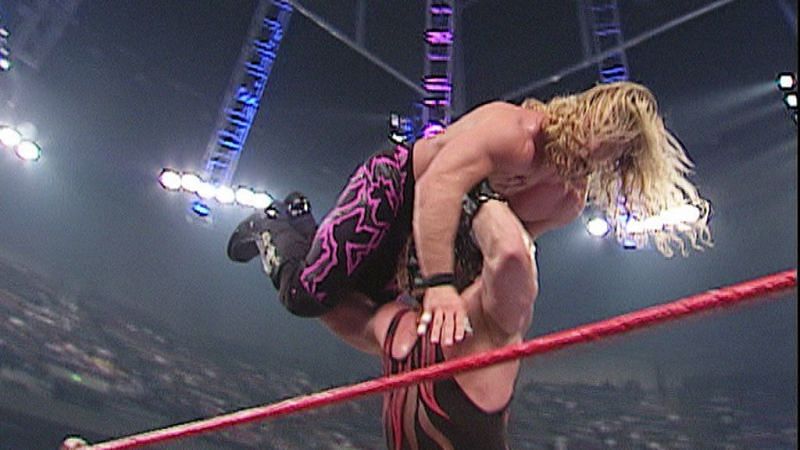

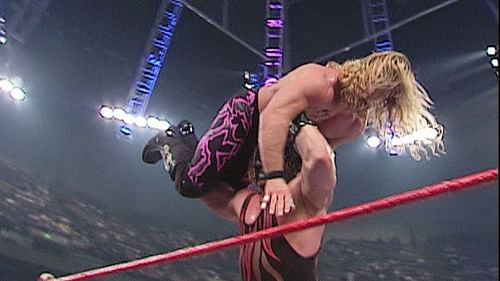

Though not on this week's ballot, in the spring, voters in Knox County, Tennessee will decide whether Glenn Jacobs, known for the past 20 years to fans of fake fighting as the Devil's Favorite Demon himself Kane, will become their next mayor; in honor of that fact, we'll be taking a look at his December 10, 2000, Last Man Standing match versus a man whose name has been on the lips and fingertips of wrestling enthusiasts worldwide this week, Chris Jericho.

Requiem for 2000 WWF

Before getting into the specifics of this feud, this match, and this event, let's take a moment to appreciate the quality of the World Wrestling Federation's physical competition at the dawn of the new millennium.

It's a year whose pay-per-view action is sandwiched between the January's Royal Rumble (whose WWF Championship Street Fight and Tag Team Tables Match are surefire future entries for this feature) and December's Armageddon, the home of today's match as well as the six man Hell in a Cell Match for the WWF's top prize.

As discussed in our last feature on WCW's eight-minute parade of juvenile humour and ill-prepared props, the year 2000 found the McMahon family all but completing their rout of their southern rivals largely due to the quality of the wrestling itself.

Fortunes began to swing in 1998 with the ascension of Steve Austin to the company's marquee performer, and Austin's continued defiance of his evil boss throughout 1999 just widened the growing gap between the competing companies' ownership of professional wrestling on cable television.

In November of 1999, however, the unthinkable happened: in storyline, Austin was run down by a renegade driver in the garage of the Joe Louis Arena in Detroit, Michigan. But, in reality, Austin was finally taking time off to heal a litany of injuries accrued over his rise to the top of the World Wrestling Federation, primarily lingering issues from an errant Owen Hart piledriver breaking Austin's neck in August of 1997.

For two and a half years, the World Wrestling Federation was synonymous with Stone Cold Steve Austin but, for the first time since his debut, the Rattlesnake could not carry the company's television programming.

The Undertaker, meanwhile, tore his pectoral muscle in late 1999, forcing him to stay home for the longest stretch of time since his seven-month 1994 hiatus, from the 1994 Royal Rumble until that year's SummerSlam contest against his evil doppelganger.

It was a power vacuum at the top not unlike the early-to-mid-1990s, when heroes like Hulk Hogan, Randy Savage, Scott Hall, and Kevin Nash departed Stamford for the grander guaranteed paychecks offered by Eric Bischoff.

That era promised a "New Generation" of superstars to fill the void, but the company delivered little on that promised; the year 2000, however, more than made up for their missing main eventers with younger talent ready to innovate at all costs. Triple H cemented his main event status early and often, while younger talent like Matt and Jeff Hardy, Edge, Christian, and a bevvy of WCW refugees redefined the mid- and undercard.